Would a music television show like ‘Recovery’ work today? [op-ed]

![Would a music television show like ‘Recovery’ work today? [op-ed]](https://images.thebrag.com/cdn-cgi/image/fit=cover,width=1200,height=800,format=auto/https://images-r2-1.thebrag.com/tmn/uploads/Music-Television.png)

Bring back Recovery! Bring back Recovery!

It’s the catch cry for music-lovers of a certain age range, either those who fondly recall being hungover and rolling out of bed (or ‘off mattress’) to be blasted by three hours of live television more madcap than whatever they got up to the night before, or those slightly younger fans who had recently graduated from morning cartoons to something a little more teenaged and exciting, eyes still waking up, brain still in bed, mouth tasting like catnip, lap holding a bowl of cereal so sugar-laced, their pancreas is on high alert to start pumping insulin through cells.

I’m in the latter group, and one of the biggest supporters of the return of Recovery. Last year I wrote a short column titled ‘Australia desperately needs a show like Recovery’ and argued that it would give invaluable exposure to hundreds of Aussie artists, plus those overseas indie acts who don’t really have many/any national promotional opportunities when touring Australia.

While this remains true, as does my firm belief that what the kids of today (yup!) need is a psychedelic dose each Saturday morning of the type of freewheeling madness that use to jolt us into the weekends, it’s probably wishful thinking to expect that a show like Recovery could work on free-to-air Australia TV in this day and age. And yet…

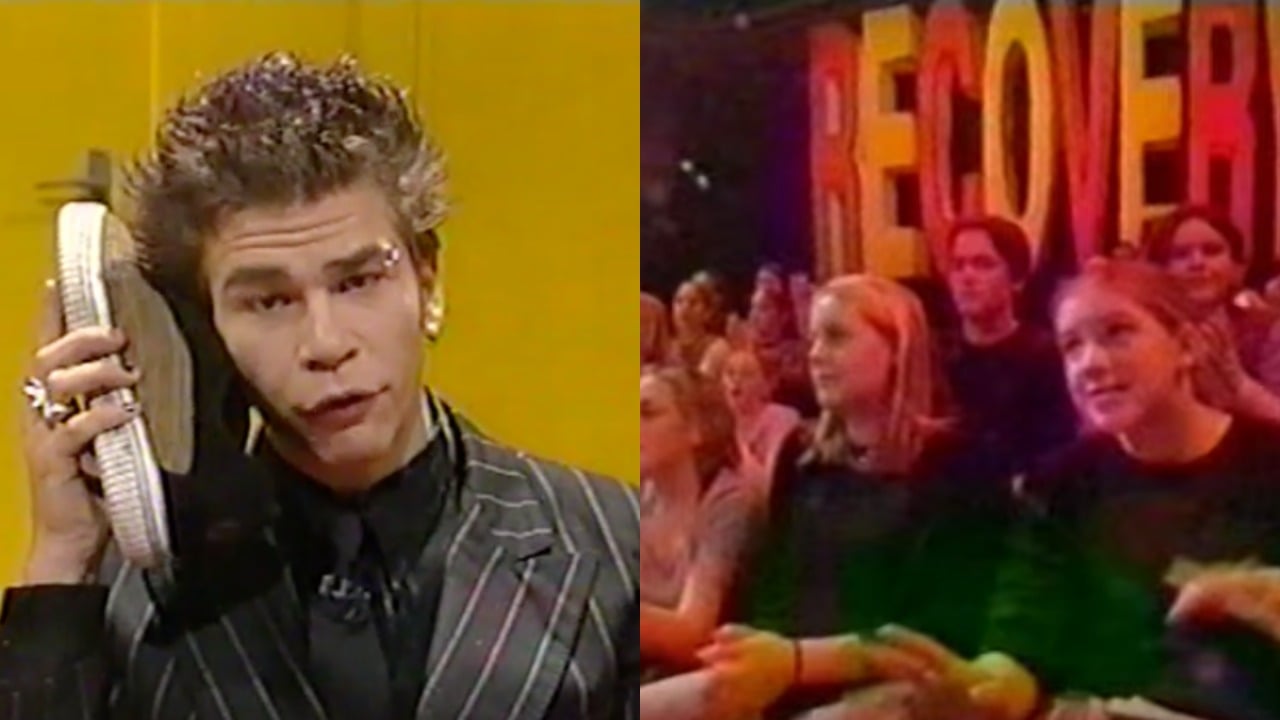

For those who weren’t cognizant between April ’96-’00, Recovery was three hours of live mayhem hosted by Dylan Lewis and Jane Gazzo (as well as a few others). There were live bands who played in front of beautifully custom-designed sets that looked like the band members had shrunk and fallen into a world made up of their own record sleeves, interviews with clearly sleep-deprived, hungover musicians, video clips, tour dates, endless references to ‘Monkey’, film reviews from Leigh Whannell – the guy who would end up creating the ‘Saw’ franchise – and a lot of liminal nonsense that is impossible to explain with any clarity.

The show changed formats numerous times, starting in a house in Sydney, moving to a Melbourne studio in front of a live audience, moving back to a house, and slowly slipping in more video clips and less live bands, until the show’s final months were just a collection of techno clips, with no hosts, no studio audience, no charm, and no resemblance to ‘Recovery’, bar the logo.

But for a brief window, it was the greatest live music television show of all time: an insane rollercoaster ride that was at its best when it flew off the rails. One week, Green Day were in studio for an interview when they spotted the gear set up for the house band and asked the audience if they wanted them to play. You can guess the response. They then ripped into an uncensored version of ‘The Grouch’, a song where the chorus repeats “the world owes me, so fuck you” numerous times. This was Saturday morning TV, usually the domain of Porky Pig cartoons and gardening programs; not surprisingly, ABC executives had conniptions and almost yanked Recovery off the air.

Recovery ended close to two decades ago, and it’s been that long since a free-to-air music show of its ilk has been successful in Australia.

Recovery’s spiritual successors The 10:30 Slot and jtv each lasted less than two years on the ABC, while Network Ten tried to meld live performance, live hosts, and video clips in a similar way with Pepsi Live (2000-2003) and Ground Zero (1997-2001).

Nothing stuck, and it appeared that Australian music TV only worked in the long run if it was:

a) 100% video-clip based, such as RAGE, which has been on air since 1987.

b) 80% clip-based (like Video Hits) with a 20% window where a host introduces clips and sometimes phone competitions where you call in to win a prize pack containing a copy of Salt ‘N’ Pepa’s new album, a 90210 Brenda doll, a TV Hits subscription, Hit Machine volume 4, 100% Hits volume 10, a copy of Smash Hits, and Hits From The Bong: the Cypress Hill VHS. Plus some Allen’s lollies, for some reason.

It’s not as if Recovery was an anomaly. Countdown was its forerunner of sorts. It was the perfect blend of live TV, a shuffling stammering live host, live interviews, a live audience, fresh video clips, and… well, mimed music. But the artists showed up on set and pretended to play. It seems live. The show lasted from 1974 to 1987 and was instrumental in the success of countless Australian bands and record labels, as well as launching international acts in our market. That show also ended 32 years ago.

And as Lou Reed talk-sang, those were different times.

There has been the odd recent stab at recreating a similar formula, like the short-lived Jam TV that launched last year in Adelaide only. They just broadcast footage sourced from local gigs, and failed to get out of the city limits during its months-long run.

Last November, ABC launched The Set, which was hosted by triple j’s Linda Marigliano and Dylan Alcott, but they only commissioned four weekly episodes for ‘Ausmusic Month’. It was a pilot run, basically, that never went to series.

Which leads us to c).

Unfortunately, executives have discovered that the only other music-based formats that work long term on Australian free-to-air television are those based around watching people compete. On Australian TV, music is sport.

Even shows like the beloved RocKwiz and Spicks and Specks were based around competition, albeit the friendly, pub trivia type. Still, at the end of every episode there was a winner, plus you could play along at home.

Despite the visceral response humans have to hearing a certain chord change or timbre of voice, we are still trained to believe music involves competition.

There are awards nights, sales charts, best of lists from every publication that rank albums and songs from every imaginable genre, year, and continent, and there are televised talent competitions.

If the flood of reality television shows over the past two decades has taught us anything, it’s that Scott Disick has exceptional comic timing. If it has taught us anything else, it’s that we like to watch people compete with each other. Whether it’s over a soufflé, a rose, or a race around the world, we wanna see people competing. We love it when they are exceptional, and we love it even more when they are terrible.

There hasn’t been a single year since 2000 (note: the year Recovery died) where we haven’t had at least one ‘win-a-record deal’-style singing competition airing on free-to-air prime time television. Popstars opened these floodgates.

The Australian version of Popstars launched in 2000 with the aim of creating a world-beating pop group a la The Spice Girls or The Backstreet Boys. Realistically, we got an ‘O Town’ or two, but the show was still a success: lasting three seasons, and spawning Scandal’us, Bardot, and – after the format shifted to a solo competition – Scott Cain.

Each winner landed a number one single on the ARIA chart. Sophie Monk was the biggest star created by the show, with Tamara Jaber a distant, distant second. Scott Cain’s single ‘I’m Movin On’ was the best song launched by Popstars; partly because it was written by the New Radicals guy (Gregg Alexander) and featured his patented slide-to-falsetto he shoves into hits by everyone from Ronan Keating to Sophie Ellis-Bextor, and partly because Scott Cain looked and acted like a cast member from Heartbreak High.

The Popstars concept was actually created in New Zealand in 1999 and ended being sold to 38 other countries around the world. Internationally, the show was responsible for 43 #1 singles in various territories. None of the 39 versions of the show still exist, with the Germans holding out the longest (until 2015) after eleven seasons and as many number one singles. They are stubborn, the Germans.

The ‘Popstars’ groups with the best names were/are Slovakia’s ‘Seven Days To Winter’ (so emo), ‘Bellepop’ from Spain (elegant), Canadians ‘Sugar Jones’ (sounds like a solo blues singer from the Bayou, but isn’t) and ‘Excellence’ from Sweden (simple, neat, confident).

The groups from the UK version had the most long-lasting success, with both Hear’Say and Girls Aloud coming from the show, while Australian solo act Miranda Murphy almost certainly edited the show’s Wikipedia page to add herself to the ‘other notable artists’ section.

The year after Popstars was cancelled by Channel Seven, Australian Idol launched on Ten, a Simon Fuller ‘concept’ which he admitted he just nicked from Popstars. The first season was a ratings winner – the most-watched show on Aussie TV that year – and unleashed the twin powers of Guy Sebastian and Shannon Noll on the universe, not to mention the likes of Rob Mills, who hooked up with Paris Hilton at her fame peak and played a mean Danny Zuko on stage a few years back; Paulini Curuenavuli, who, with 2006’s ‘So Over You’, released the best non-Beyoncé Beyoncé single until Kelly Rowland’s ‘Work’ stole the crown the following year; and Cosima De Vito, who later mortgaged her family home to pay to independently release a Cold Chisel cover that she had no chance of recouping the money from – parental love knows no bounds. To quote Frank Sinatra’s review of the 2003 season of Idol, it was a very good year.

In 2004, the producers of Popstars saw the veritable star factory Idol had built and wanted back in, launching Popstars Live. The series was a ratings disaster, leading Channel 7 MD David Leckie to theorise this was due to the generally supportive nature of the judging panel. Aussies want to see dreams crushed, dammit, not supported! The producers pressured the judges to be… well, more like Idol‘s Dicko, and many of them, including Christine Anu, flatly refused. She quit the show, releasing a statement which read: “I chose to play a positive role model and wanted to encourage these young people in their endeavours, rather than criticise them,” expressing relief that she could return to focusing on her own music. Within a few weeks the show was bumped from the Saturday night schedule in favour of a series of nature documentaries.

Idol however, kept pumping for seven seasons, introducing Australians to the likes of Casey Donovan, Anthony Callea, Damien Leith, Jess Mauboy, Ricki-Lee Coulter (who stole the non-Beyonce Beyonce crown in 2012 for ‘Do It Like That’), Lisa Mitchell, Dean Geyer, Lee “Wasabi” Harding, Owl Eyes (not her birth name), Wes Carr, Stan Walker, Em Rusciano (better known as a comedian these days) and Kate DeAraugo (better known as a tomahawk-wielding meth addict these days).

The show also inspired this excellent sentence on Wikipedia: “A ‘touchdown’ was awarded by judge Mark Holden when, in his own opinion, a contestant’s performance was particularly good.”

The X Factor joined the party in 2005, but gave their first recording contract to a boy band named ‘Random’ and therefore was cancelled by Channel Ten after only one season. Given Ten also had Idol, they might have been pushing their luck with a second show that was basically a carbon copy. In 2010, with Idol having finished the year before, Channel Nine took over the rights for X Factor, and managed to keep it on air for seven more seasons (the same length run as Idol), giving careers to Dami Im, Reece Mastin, Samantha Jade (although she was already somewhat successful) and future ‘Bondi Caveman’ host Altiyan Childs.

The Voice, launched in 2012, is the only one of these shows to remain on air, although its appeal lies in a revolving cast of celebrity judges, such as Seal, Keith Urban, Kylie Minogue, Benji Madden, Delta Goodrem, Kelly Rowland, Guy Sebastian (traitor!), Will.i.am, and Boy George. Doesn’t that sound like the lineup for the worst charity single ever?

There will be another one launched soon. Then another one. There always is.

The appeal of these shows is obvious: they offer a rags-to-riches scenario, playing it out week to week on TV and in gossip magazines, while we debate, and hate, and vote along. The earlier stages of the competition also provide us with some truly untalented talent, proof positive that “never give up” and “follow your dreams” are two of the worst pieces of advice to give anybody.

It’s addictive television, that’s for sure.

Let’s put aside that the entire structure is built upon toying with the dreams of a never-ending flood of hopefuls looking for a shot and not understanding the mechanics of the industry they wish to work in.

Let’s put aside the moral and legal quagmire of ‘winning’ a legally-binding contract where the pay rates and time-length are non-negotiable, and you are restrained from trading in your chosen field for a set period afterwards even if you don’t ‘win’ the big prize.

These programs have, ultimately, been good for the Australian music industry. No, really. They pump a lot of money into the local economy. They get people buying Australian music. That’s certainly nothing to sneeze about.

But we still need a show like Recovery. A show where music isn’t a competition, it is something to be adored and celebrated and dissected and shared. Australian bands need a place to play live on national free-to-air television. Saturday morning TV needs to be good again. Eyebrow rings need to return. Actually, scratch that last point.

Unfortunately, the world has moved on. Among those things receding from culture are: free-to-air television, rock music in general, and three-hour live TV shows. Plus eyebrow rings. The monoculture is dead, as is appointment viewing. Everything that Recovery leaned on has lost currency in the world. The most popular ‘rock’ bands in the world peaked 20 to 40 years ago: Foo Fighters, Green Day, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, Coldplay, Queen, The Rolling Stones, The Who. These are the bands selling out stadiums. Ed Sheeran and Taylor Swift might be the only current pop stars who sell out stadiums on a global scale that have ever held a guitar on stage.

Not that a show like Recovery needs such an audience. As the viewing figures for TV plummet, it actually makes much more sense for such a show to be launched: something that will build a solid, niche audience that might actually rival those of shows intended to be mainstream.

If you build it, they will come. Well, they might. I’m hopeful that a show like Recovery will return, and that it will be a success. I’m also hopeful that computers will never replace books, humans will always want music on physical formats, and that Home and Away will never be cancelled.

In early 1962, the senior A&R man at Decca Records told the manager of The Beatles that guitar groups were on the way out. It certainly looked like that in 1962, as it does now, in 2019. But we all know what happened next.

Maybe “never give up” isn’t such terrible advice after all…