Why are none of the top 10 music-video debuts in YouTube history from hip-hop artists?

Global digital-media consumption is accelerating at a rapid-fire pace, and music videos comprise just a tiny microcosm of that phenomenon: six of the top 10 music-video debuts of all time, defined by number of YouTube views within 24 hours, took place within the last six months.

Here’s a full list of the top 10 YouTube debuts of all time as of April 29 (asterisked entries were released in the last six months):

- *BTS (ft. Halsey)—”Boy With Luv” (74.6 million views in 24 hours)

- *Taylor Swift (ft. Brendon Urie)—”Me!“ (65.2M)

- *Blackpink—”Kill This Love” (56.7M)

- *Ariana Grande—”thank u, next” (55.4M)

- BTS—”Idol” (45.9M)

- Taylor Swift—”Look What You Made Me Do” (43.2M)

- *Twice—”Fancy” (42.1M)

- *Guru Randhawa (ft. Pitbull)—”Slowly Slowly” (38M)

- Blackpink—”Ddu-du Ddu-du” (36.2M)

- Psy—”Gentleman” (36M)

There are a few interesting patterns to glean from here. Not only are three artists repeat winners on the list (namely BTS, Blackpink and Taylor Swift), but 70% of the list also comes from artists outside the U.S. industry bubble, i.e. from Korea, Japan and India.

Most importantly for today’s topic: all of the top 10 videos come from the more or less “traditional” pop world—and aside from Pitbull’s Indi-pop feature, hip-hop/rap is nowhere to be seen.

In fact, the most successful hip-hop video debut of all time isn’t even a proper music video at all; it’s an audio-only version of Eminem’s diss track “Killshot,” which garnered 38.1 million views in its first 24 hours.

The picture looks even bleaker for hip-hop if you limit your scope to official Vevo channels. According to Wikipedia—and as I confirmed with a Vevo rep for this newsletter—the top five Vevo debuts come from Taylor Swift, Ariana Grande and Adele; the remaining two entries aside from those included above are Adele’s “Hello” and Swift’s “Bad Blood,” both released in 2015.

The rapper with the largest Vevo debut is Nicki Minaj, who ranks at #6 with her video for “Anaconda”—which was released back in 2014 and got 19.6 million views in its first 24 hours, falling behind the more recent debut for “Me!” by nearly 70%.

After Nicki Minaj, the next highest rappers on the Vevo debut charts—namely Drake, Eminem and Childish Gambino—are only ranked around #30 and below.

I was surprised to learn about this gap because hip-hop has garnered a reputation for being one of the most-streamed genres in the U.S., let alone in the world. Charts elsewhere suggest that hip-hop dominates streaming on a global scale: not only did Nielsen find that eight of the top 10 U.S. albums of 2018 were by hip-hop artists, but the top three most-streamed artists on Spotify that year were also rappers (Drake, Post Malone and the late XXXTentacion). It’s been widely covered that record labels are engaging in a ongoing signing frenzy for rap hits as a result, with Def Jam even going so far as to establish its own “rap camp” to break multiple rappers on their roster simultaneously.

The “SoundCloud rap” community in particular has cultivated a reputation for chasing online clout and virality at all costs. Arguably more than any other genre, hip-hop embraces rapid-fire, meme-friendly release and circulation strategies to maximize streams and impressions. Historically, rappers have also been early adopters of influential short-form video platforms like Snapchat, Vine and TikTok; as New York Times pop critic Jon Caramanica wrote, “practically every significant music-internet innovation of the last 15 years took hold in hip-hop first.”

Then why has the tech-forward world of hip-hop hit a ceiling on a chart that seems literally made for the genre—measuring viral, 24-hour engagement—on a platform that combines two of the genre’s biggest marketing strengths, video and streaming?

It’s not like YouTube and Vevo don’t like hip-hop; quite the opposite, in fact. According to BuzzAngle’s 2018 year-end report, hip-hop/rap had the largest market share of all video streams that year at 22.8%, compared to 21.8% for Latin, 16.6% for pop and 11.9% for R&B. YouTube’s music team is also stacked with hip-hop veterans who constantly have a pulse on emerging sounds and cultures, including but not limited to Lyor Cohen (former co-president of Def Jam), Tuma Basa (former global programming head of hip-hop at Spotify) and Naomi Zeichner (former editor-in-chief at The FADER).

But based on my own research and conversations online and IRL with music enthusiasts, I’ve come up with three higher-level hypotheses for why the first-day performance of hip-hop videos on YouTube remains so limited. I think it boils down to two main reasons: fundamental, ideological differences in how hip-hop versus pop artists approach marketing and fan engagement, and the rising influence of regional music cultures that is shoving American music away from being the industry default.

? Hypothesis #1: Pop artists tend to premiere their music videos on the same day as their singles to maximize first-week hype—while rappers tend to air out tracks for a few weeks to gauge audience feedback first.

Earlier this week, I wondered aloud on Twitter why the YouTube/Vevo debut charts were such hip-hop deserts. The Newbury Comics account (!) wrote an interesting reply:

Oftentimes, the hip-hop video drops long after streaming has taken off. In the pop world, the video is more often part of the premiere.

— Newbury Comics (@newburycomics) April 29, 2019

I thought this was such a smart observation, but couldn’t find any research online to corroborate the claim—so decided to do a little digging myself. Indeed, I found that the differences in average wait time between a single and video release date in mainstream pop versus in hip-hop are like night and day.

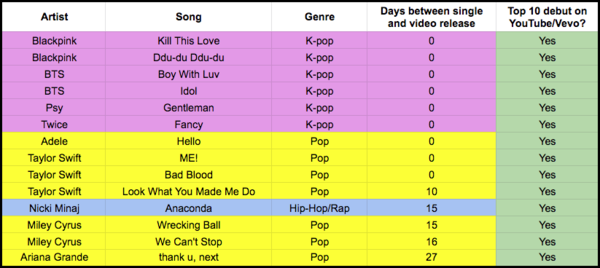

The following tables below show the lag time post-single for 1) the top 10 music-video debuts on YouTube and Vevo, and 2) a sampling of the top rap videos overall, that did not rank highly on the debut charts. Both are color-coded by genre, and arranged in descending order from shortest to longest lag time.

First, let’s look at the best YouTube/Vevo debuts of all time:

The Newbury Comics reply guessed correctly: the majority of the top video debuts were released on the same day as their corresponding singles.Note that every major K-pop video in this table was a same-day premiere. This is standard practice in the local industry, with high-profile, simultaneous single/video releases often signalling the pinnacle of an artist’s “comeback cycle” (i.e. any new release)—building up hype with a variety of teaser content beforehand, followed by weeklong broadcast promotion afterwards.

Each K-pop group also has a vast network of Korean and international fan “armies” that excel at digital coordination, particularly for pumping up first-day streams across the board. (For a group-specific study: Chartmetric found in 2017 that differences in fan behaviour helped BTS become two to three times more “viral” than One Direction.)

Because Taylor Swift also has a rabid fan base, it makes sense for her not just to adopt a similar strategy of releasing singles and videos simultaneously, but also to make such releases a true event—e.g. going so far as to launch a cryptic countdown clock on her website 13 days before the premiere of “Me!”. While “Look What You Made Me Do” had a 10-day single-to-video lag, it still managed to break records at the time, likely because the controversial brand change behind Reputation generated its own buzz separately from the music itself.Ariana Grande is the biggest outlier, having waited 27 days between the single and video release for “thank u, next.”

But the artist compensated for this lag by similarly treating the video release as a real-time and communal event, rather than just another on-demand product. She released the video via YouTube Premiere, attracting more than 829,000 simultaneous viewers and 516,000 chat messages within just a five-minute window, a record that has yet to be broken on the video platform.

Coupled with the video’s string of early-2000s cultural references, it’s no surprise that “thank u, next” still managed to rise to #4 for all-time YouTube debuts and #2 for Vevo debuts.

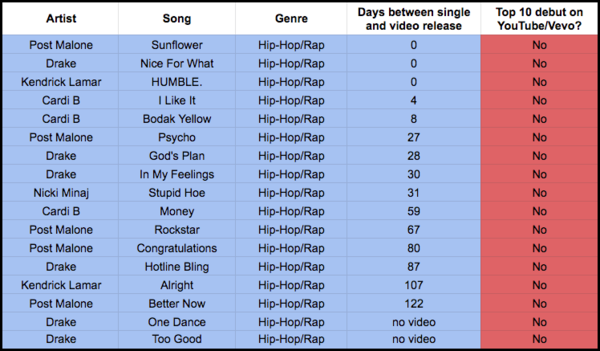

Now, let’s look at the single-to-video lag time among the videos for some of Billboard’s highest-charting rap singles—none of which are top-10 YouTube/Vevo debuts:

This paints a nearly polar-opposite picture from the first, pop-centric table. While most of the top video debuts of all time had no lag time post-single, the above rap hits preceded their music video releases by six or more weeks on average.

With the exception of “Nice For What,” all of Drake’s music videos came out 28 or more days after their corresponding singles were released on streaming platforms. In fact, two of his most popular songs, “One Dance” and “Too Good,” don’t even have any official videos at all.

One other systemic obstacle holding Drake back from a record: streaming exclusives. The video for “Hotline Bling,” which spent 18 consecutive weeks on Billboard’s Hot Rap Songs chart, was released as an Apple Music exclusive seven days before landing on YouTube, with a total lag time of 87 days. This may come across to some as a peculiar strategy, especially because none of those first-week views were reported to Billboard or Nielsen—but as I’ll discuss later in this newsletter, hip-hop artists tend to embrace exclusive content deals much more than other genres in pursuit of artificial scarcity.

Similarly, Post Malone is one of the most-streamed artists in the world right now, currently ranking #4 in the world on Spotify, but has never made a top-10 video debut. This is likely because he waited more than two months to release the videos for many of his most popular singles, including “Rockstar,” “Congratulations” and “Better Now.” The one exception is “Sunflower”—for which it made sense to have no single-to-video release lag, given the song’s important promotional role in the film Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

At large, Drake, Post Malone, Cardi B and many rappers of similar stature seem to be chasing quantity and ubiquity of content—best achieved through tactics like placements on streaming playlists and spins on terrestrial radio—such that a given video release often feels just like a drop in a sprawling content bucket, rather than a massive, standalone event. In the next section, I’ll discuss how rap’s reputation for flooding the market limits its performance on YouTube, even if video overall remains a crucial fan-engagement strategy for the genre.

(If you’re interested in playing around with or expanding on the above data for yourself, you can access the spreadsheet by clicking here.)

? Hypothesis #2: Flooding the market with content, rappers rely heavily on short-form video and editorial playlists for exposure. YouTube is optimised for neither.

One of the most extreme manifestations of rap’s modern marketing ideology is the “Pump Plan”—a ten-step marketing template first tested on SoundCloud rapper Lil Pump, and now formally implemented on a regular basis at Capitol Records imprint Inzei Records. Tasked with making a relatively minor rapper go viral, the plan includes tactics like WorldStarHipHop promotion, influencer campaigns on TikTok (and formerly Musical.ly) and “controversy projects,” i.e. artificial feuds among artists that do nothing but cause drama for drama’s sake.

It sounds as vapid as you can get, but is nonetheless instructive—particularly because of which companies it leaves out. Recent features about the Pump Plan in Vulture and Genius make no mention of YouTube as an important pillar of the strategy.

As I mentioned in the previous section, many rappers today are looking to achieve maximum ubiquity on a minimal budget. While YouTube videos are easily sharable, my hunch is that the platform currently does not take up much mindshare among music fans as the primary format for ubiquitous, rapid-fire video sharing (read: memes). In contrast, the UX behind more short-form-friendly apps like TikTok and Instagram is arguably more conducive to decentralized, fan-driven promotion.

As a result, some rappers might use YouTube as a tool for inking third-party brand partnerships that have greater short-term ROI than a singular music video. For instance, as Amber Horsburgh suggested in a hypothetical case study on Yung Lean, rappers looking to reach more casual audiences (at the “just-aware,” “familiar” and “consideration” stages) will often decide to pursue short-form content partnerships with brands like 88 Rising, Noisey, Mass Appeal, Genius and Lyrical Lemonade, instead of dumping thousands of dollars into a video themselves that has a smaller chance of reaching new viewers.

At large, many rappers also operate under the assumption that the best way to build one’s audience is to oversupply the market with a higher quantity of songs, which naturally makes said rappers focus more on audio- rather than video-first channels for promotion (there’s a reason a whole generation of rappers was named after a platform for audio, not for video).

There’s no shortage of editorial playlist and curation support for hip-hop across streaming services—from more underground-focused platforms like SoundCloud and Audiomack, to mainstream channels like Tidal, Spotify’s RapCaviar and Apple Music’s hip-hop radio shows from veteran DJs Charlie Sloth and Ebro Darden.

In contrast, music curation is largely decentralised on YouTube, making the platform fall short on the type of official playlist support that hip-hop artists crave. Other genres like electronic music have a robust ecosystem of influential curators on YouTube—think Trap Nation, or the channels owned by AEI Media—but there are few equivalents in the rap world. As one Twitter follower suggested:

I’d say the lack of playlist structure. On streaming platforms, the numbers may not be due to actual demand. Instead, they could just be a product of users being force fed through playlists. On Youtube, the structure isn’t there for that. You HAVE to choose.

— Payus N. Mind (@PayUsNoMind) April 29, 2019

As a result, the artists with the most rabid, highly-engaged and highly-coordinated fanbases—e.g. Taylor Swift, Ariana Grande and many K-pop groups—win out on YouTube video debuts not just because of their same-day release strategy, but also because they arguably don’t rely as much on playlists.In fact, many of these same pop artists are increasingly trying to co-opt hip-hop marketing strategies for their own benefit.

“My dream has always been … to put out music in the way that a rapper does,” Ariana Grande recently told Billboard. “I feel like there are certain standards that pop women are held to that men aren’t. We have to do the teaser before the single, then do the single, and wait to do the preorder, and radio has to impact before the video, and we have to do the discount on this day, and all this shit. It’s just like, ‘Bruh, I just want to fucking talk to my fans and sing and write music and drop it the way these boys do. Why do they get to make records like that and I don’t?’ So I do and I did and I am, and I will continue to.”

In the other direction, despite their passion for flooding the market, many rap artists are also trying to cash in on the artificial scarcity and suspense at which pop stars excel (e.g. Taylor Swift’s countdown clock, Ariana’s YouTube premiere) by pursuing exclusive content with streaming services. Hip-hop artists are some of the earliest and most avid adopters of exclusive windowing deals with Apple Music and Tidal, which often provide the benefit of more upfront money at the expense of engagement.

? Hypothesis #3: YouTube has one of the most international user bases in the world—no longer framing U.S.-based music as the industry default.

As I mentioned at the top of this newsletter, 70% of the top 10 YouTube music-video debuts of all time come from artists outside the U.S. industry. This is likely because YouTube touts one of the most international streaming user bases in the world—a status reflected in its global charts for artists, songs and music videos, all of which are publicly accessible.

As of today, only 11 out of the top 30 songs, nine of the top 30 artists and eight of the top 30 music videos on YouTube are from the U.S. and Europe; India, Korea and Latin America seem to be in heated competition with each other for the remaining top slots.

YouTube’s international artist development program Foundry also notably covers multiple continents, featuring artists from Japan, Korea, Mexico, Haiti and Lagos in addition to the dominant Western markets.Indian record label and film production company T-Series owns the most-watched YouTube channel in the world, having garnered nearly 70 billion total views to date and adding over 100,000 subscribers a day, according to SocialBlade.

At large, YouTube has gained significant adoption across India’s entire population: in an interview late last year, Gautam Anand, managing director of YouTube APAC, shared that 85% of the country’s internet users use the video platform. Even the standalone YouTube Music app hit three million downloads in India within a week of its official launch last month.

Latin artists also dominated the YouTube artist charts in 2018. According to Rolling Stone, the three artists with the most views on the platform—Ozuna (20 million subscribers and 8.7 billion views), J Balvin (18M subs, 7.1B views) and Bad Bunny (13M subs, 7B views)—were all Spanish-speaking.

Given this background, one potential path forward for rappers and other hip-hop artists to break into the top-10 debut charts is through features with Korean, Latin and Indian artists, as Pitbull pulled off successfully. At large, features are a tried-and-true strategy for maximising audio streams in record time, and there’s no reason YouTube is an exception to that rule.

One unanswered question I have is what the actual retention of these YouTube viewers looks like on a regional level. For instance, I recently heard about a major electronic artist who received a significant proportion of views on one of his music videos from India, but very few of those India-based views ended up lasting more than ten seconds. I would love to see stats on market-by-market viewership retention on YouTube, and what insights that reveals about regional consumer behaviour (e.g. are viewers in certain markets more like to skip around than in others?) and the nature of conversion from views to fandom.

And as for who will most likely be the first rapper to break into YouTube/Vevo’s top five video debuts, if that ever happens…

I think the top contenders will be rappers like Cardi B, Nicki Minaj and Drake who not only are associated with “traditional” pop stars more frequently than their peers, but have also released collabs with many international artists (e.g. Drake x Bad Bunny, Cardi B x Ozuna, Nicki Minaj x Farruko x Bad Bunny) and are uniquely positioned to continue “mainstream-ifying” other forms of international crossovers.

While hip-hop and rap certainly continue to lead the way in audio streaming at large, pop still rules the art of the music video premiere—and the tactic’s international sensibility will continue to unveil new models of fandom and engagement that rappers and their peers should watch closely.

This article was first published via Cherie Hu’s independent newsletter.

This article originally appeared on The Industry Observer, which is now part of The Music Network.