Forget Napster, it was iTunes that held the record industry to ransom

Napster is written firmly into the history books as the bad guy. The service relied upon piracy; it was treated as a near fatal blow to the music industry, and the hard-working artists that fuel it. Napster was taking money out of the mouths of musicians, and anyone who downloaded a mislabelled Lit MP3 was complicit in the crime.

The arrogance of its creators when dealing with early copyright claims from Metallica and Dr Dre made them seem like rogue pillaging pirates rather than young entrepreneurs who were being targeted by multi-millionaires who didn’t understand the mechanics of how the software worked.

Napster was a threat, but perhaps the biggest threat it posed to the music industry was that it wasn’t taken seriously enough as an irreversible technology leap.

Napster’s reputation never escaped from the realms of the technology-savvy. You needed a decent internet connection to download music from the service, you also needed a willing accomplice, someone to share the song that you were attempting to download. You needed to know how to use the program, plus an MP3 player. You needed to know that Wendy_Clear_Blink182_128.mp3 might not be what you expected.

There were a lot of steps. A lot of variables. A lot of fake Radiohead songs. In the pre-Y2K wasteland of dial-up modems and constellation screen-savers, it took half an hour to download one four-minute song. And that’s all predicated on the assumption that Mum wouldn’t pick up the phone to call Nan twenty minutes into the download.

Sure Napster was free, but it also traded in a time-based economy, and the costs were high. Before the iPod, MP3 players were in their infancy – until the end of 1999, most handheld units were 32MB systems, meaning they could only hold an album’s worth of songs, assuming you compressed the files to sound like someone was playing them through a tin speaker three houses down. If you want portable music, you’d be better off carrying around a Walkman.

But these were fast times. Record labels and copyright holders only saw the profits they were losing from Napster, both as a company and program, existing. They didn’t look into the recent past, and see how quickly peer-to-peer file sharing had infiltrated. They didn’t look into the future and see how this technology would continue to become more user-friendly, how quickly ideas like this spread. How information wants to be free.

Record labels traditionally look backwards to understand trends; their business model is based upon catalogue sales of music recorded decades ago, their projections are based upon past performance. Their risks are small and measured. Companies like Apple look to future trends: like a quarterback throwing a pass, they aim at where the receiver will be, not where they currently are.

At the turn of the century, the record industry was in flux, but they thought they were at war. They tried to take down a company who pointed toward the future, instead of quickly adapting to this type of technology. Napster showed them the path, and had they paid attention, they could have saved themselves. Instead, they tried to destroy the threat, thinking that if they squashed the singular company, the larger technology would be killed along with it.

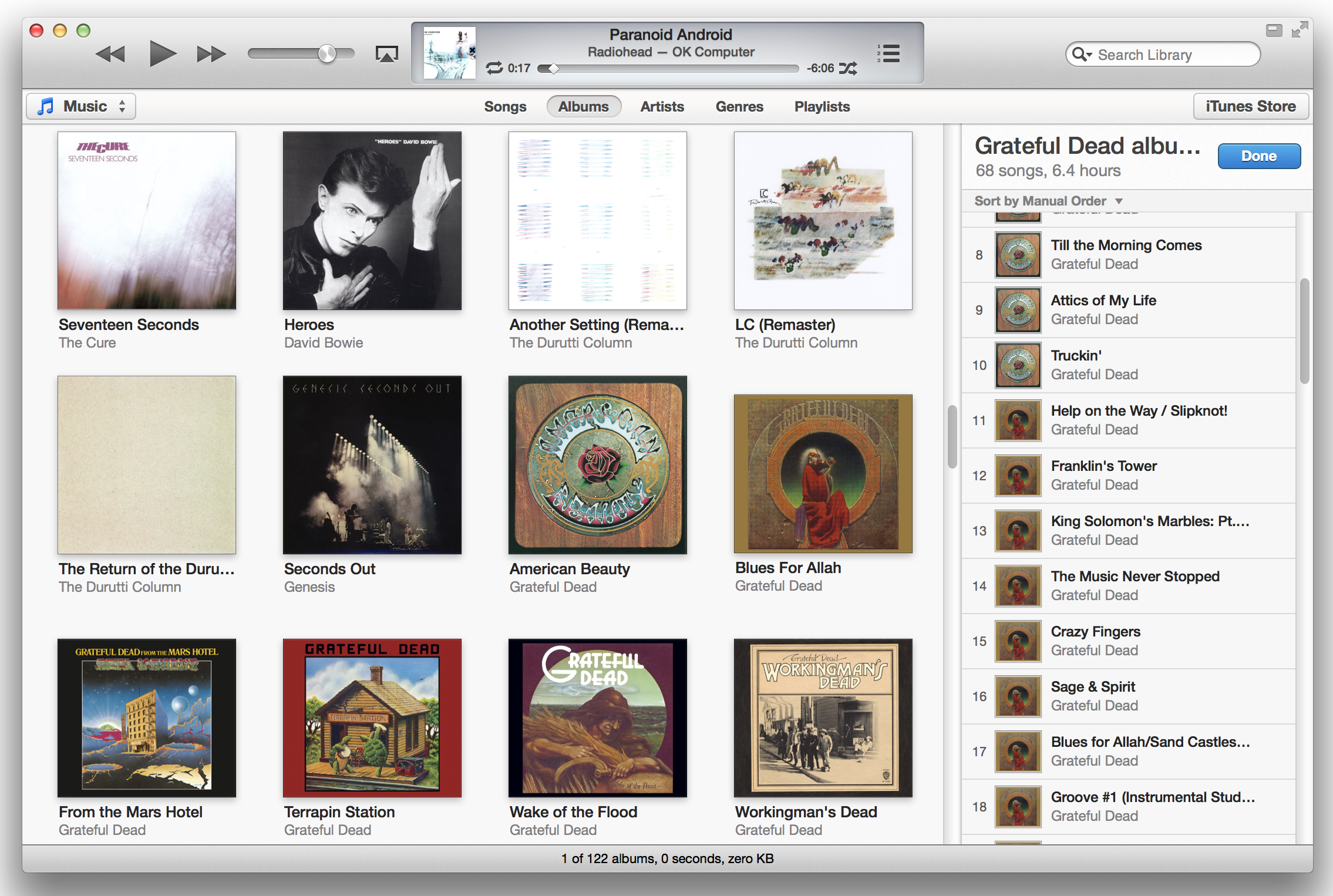

iTunes launched as a program in 2001, and was touted as a way to rip music from your CDs, and store them all in one central location – much like a jukebox. The idea was that, with the use of a CD burner, you could then compile your own mix CDs, or simply keep a handy collection of your own (presumably legally purchased) music on a central hard drive, without needing to resort to those clunky sharp CDs that had slowly taken over swaths of storage space in the lounge rooms and basements of houses around the world.

Of course, you could also use iTunes to play and store illegally gathered files from Napster and the like, plus any music ripped from CDs you borrowed from friends. In a way, Apple were taking ownership of music storage, curation, and even the playing of it. A cheap computer hooked up to a decent speaker system could immediately be transformed into a jukebox containing thousands of hours of music.

For two years, users were trained in the art of iTunes: fastidiously compiling libraries of music, which the Gracenote system automatically labelled in a neat, appealing way. Your music collection was now a searchable, alphabetised catalogue, one you could add to easily. It was a new way of collecting music, of being nerdy about music, and if an illegally obtained track or ten made their way onto the list, or a CD ripped from a friend’s collection sat among your own in the iTunes library, well, what’s the harm? iTunes certainly didn’t make the distinction, and once everything was in this neat and ordered catalogue, neither could anyone else. ‘Everything In Its Right Place’, to quote that Kid A song you got from Napster. “Rip. Mix. Burn” was the instructive slogan for iTunes in the early days, and they didn’t seem to care just what you were ripping, or who you were ripping it from.

Then the iTunes store launched in April 2003, and immediately devalued music further – ironically, by putting a price to these files. The service was touted as a legal alternative to Napster and its contemporaries, whose legal status was well documented enough to scare off would-be users afraid of being taken to court for downloading a Mission Impossible II song. The price of a single song was set at 99c in the US, $1.49 in Australia. The same program you had been using to catalogue your music had suddenly turned into a store, and you could buy anything you pleased.

This loose distinction between MP3s you’d purchased from the iTunes store, songs ripped from CDs, and files taken from other dark corners of the web was the first major step in training fans to want access to music, not ownership of music. Although you were downloading a file, which you then owned, the hurtle of there being no physical item for which you were paying was enough of a shift in perception that people became accustomed to using a music service, rather than paying for a singular item.

The fact you were paying, that it all went through one central store, that the artists were making money from these legal sales was a small enough leap in logic to appease music fans use to buying records at department stores. It was the future – a utopia of endless choice unencumbered by geographic limitations, rather than the dystopian, legally-murky world of file sharing and piracy.

Ever since the birth of the record industry, labels have had a reputation as being faceless corporate entities that takes advantage of workers and shareholders, ripping off artists, caring only about maximising return on investment. This is an admittedly harsh viewpoint, but at least in this reading, record labels have a very real financial investment in the product they are selling. At the most cynical, they act as banks — advancing credit in exchange for interest — or as holders of a share portfolio, where the records they pay to make and distribute fluctuate in market value based on external factors.

Apple only has stakes in the record industry as a whole. The success or failure of any specific artist, or record label, is of no consequence to them. They bought the entire industry. iTunes trades in the sale of music files, the actual music contained doesn’t matter, as long as they have the majority of it available in order to be the prominent store. The record labels are promoting the product, Apple just makes it available. They don’t even do that, as it is the labels who organise the digital distribution, the promotion, who even spread the individual sales links. iTunes is an automated store that don’t even stock the shelves themselves. They are a warehouse with endless space.

Apple was never invited into the music industry. They stormed in and started taking hostages. They saw a dire situation and provided a solution. They were the ones selling $10 bottles of water during a heatwave, and were filling them up from the taps of those they sold it to. Because the record industry was so incensed by the gall of those stealing their music, they went to war with a format, instead of accepting that the way in which people imbibed music had irreversibly changed and taking steps to capitalise on this.

They introduced copy control CDs that got jammed in PCs and wouldn’t play in car stereos; they sued Napster and similar companies, rather than either working with them, or developing their own MP3 distribution centre, and they tried to make piracy a moral issue when it was simply one of convenience and scope of access.

“Consumers don’t want to be treated like criminals and artists don’t want their valuable work stolen,” Steve Jobs said in his announcement keynote. “The iTunes Music Store offers a groundbreaking solution for both.” He understood the value of music, and so he stole it.

In hindsight, the leveraging power that Apple had over the labels was extraordinary. Who allowed them to set the price point, and to democratise it across the board, with no ongoing discussion or leeway? Who allowed them to dictate that albums cannot be locked, so that you couldn’t pluck off individual singles? Who agreed on the shockingly low sound quality, and why didn’t the labels rally for more hi-fidelity options, like FLAC and other lossless formats, especially when internet space and storage space were no longer legitimate issues? Who let Apple dictate their own cut of the profits from each sale?

Why didn’t the major labels team up and start their own store, or at least each have their own stores. They wouldn’t be competing in any new way different to the past – like with CDs, if you want to own a Mariah Carey record, you need to go to Sony — but all the labels did by allowing Apple in, was to replace their reliance on the bigger bricks-and-mortar retailers, with a digital one. And one with a self-imposed monopoly, limited overheads, and no incentive to promote one product over another. It made no sense, except that they were scrambling for an easy solution, and Apple provided one.

Much like with Spotify, by agreeing to such draconian terms, the record labels sold out their own artists in order to rescue their own dwindling profits. Unlike with Spotify, it appears to have occurred through being strong-armed by a company that understood the shifting landscape better than the players.

With Spotify, it was rather more insidious, as the labels were also stakeholders in the company, meaning they chose to sell out each individual artist’s profit margins, in exchange for the value of Spotify rising. This time, they were participants in the plan: the more music on Spotify, the more subscribers, and the more the company makes. The labels own a cut of the distribution model this time, and while they have agreed to profit sharing terms with their artists, this is a public relations move, not one based on fairness or altruism. The loss in profits through Spotify for each artist has been astronomical, and a small slice of the profits from the public floating of the company that cut into their earnings is hardly cause for celebration.

iTunes lasted a lot longer than a program/store based on such a transitional medium should have. 18 years is longer than the heyday of cassettes, which was roughly seven years — the cassette was only the dominant format in the UK from 1985 to 1992. Compact discs ruled sales for 18 years, from 1993 to 2011. As soon as MP3s became a viable format, their own demise was written – it took only a small leap to imagine that, like streaming video, there would soon no longer be the need to download a file at all.

Apple also saw this coming, and now Apple Music serves this same streaming market that replaced MP3s. They are no longer the market leaders, but maybe by shutting down iTunes and migrating users, and their catalogues curated over the past 18 years, across to this service, they will pluck away some of Spotify’s 217 million monthly users.

Apple will again serve those users who they taught to streamline their music catalogues, streaming or stolen, downloaded or ripped, into one ordered, indiscriminate list.