The sad death of liner note credits [op-ed]

![The sad death of liner note credits [op-ed]](https://images.thebrag.com/cdn-cgi/image/fit=cover,width=1200,height=800,format=auto/https://images-r2-1.thebrag.com/tmn/uploads/you-like-the-monkees.png)

The most prolific musician of the pop era played bass on roughly 10,000 records. She played the rhythm on ‘La Bamba’ in 1958; the heartbeat pulse on ‘You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling’; the beach ball bass line on ‘Good Vibrations’ (as well as all the bass on the classic 1966 album Pet Sounds, the California Girls single, and many other Beach Boys hits); the strutting bottom-end on ‘These Boots Are Made For Walking’ – she even played on the theme songs to Mission Impossible, MASH, Brady Bunch, and Batman.

Her name is Carol Kaye, although most of her life’s work has gone uncredited.

In the ‘60s, that was often the way it went. You were paid a flat fee to play on a record, often with the understanding that fans of these pop acts preferred to think that the mop-topped members on the record awkwardly holding their instruments aloft actually played the things. Carol Kaye was The Monkees’ actual bass player, but as a pre-teen Marge Simpson found out, it shatters childhood illusions when you learn they don’t actually play their own instruments.

Fast forward to 2020, and we have the same problem. But it’s not for any aesthetic or artistic reasoning, and it’s not just flat-fee session musicians not having their work publicly recognised. It’s band members, songwriters, engineers, producers, studios, string arrangers, backing vocalists – all these artists are being erased. As technology has progressed, and music has moved into the digital realm, album credits have completely disappeared.

Finding out who played the drums on a particular song shouldn’t take detective work. You should be able to pick up an album cover, flip it open and read all about it. There is a level of discovery that, for all the algorithms and genre-themed playlists, is completely missing from Spotify, Apple Music, and all the others. In my teen years, I would often take a punt on an album based solely on liking the producer, and trusting his taste to only work with like-minded, good artists.

The knowledge of how an album is created often adds, rather than subtracted, to the magic.

Knowing that all five members of Cold Chisel wrote various songs on their East album was a startling discovery for me, and it made it a lot cooler knowing that bassist Phil Small wrote ‘My Baby’, or that Jimmy Barnes wrote ‘Rising Sun’. They seemed more like a gang. If I didn’t pore over the band’s liner notes, I probably wouldn’t have even known that their retiring pianist, hidden under a balaclava on the best off, and in the shady corner of the stage when they played live, was the main songwriter in the band.

I wouldn’t have been able to appreciate the yin yang dynamic in Oasis, where Noel wrote all the songs, and Liam sang them. Or that U2, REM and Coldplay credited all their songs to all the members, as a sign of democracy, or decency, and as a way of avoiding squabbling over royalties. Did you know John Paul Jones arranged the strings on REM’s ‘Nightswimming’? Or that Prince wrote ‘Manic Monday’ for The Bangles? This may sound like music trivia, but there is nothing trivial about learning who is responsible for the music that you love.

When I went to Newcastle University in the early ‘00s, the city had numerous stores that sold cheap second-hand vinyl. These were often piled thoughtlessly in milk crates, with a catch-all $2 each written in marker pen on the side of the crate. I bought so many records based on checking out the album credits and reading that a producer, or a musician I liked was involved in the record. This is how I learned that George Harrison played the slide guitar on ‘Leave A Light On’ by Belinda Carlisle, which was a very good thing to learn.

The solution seems easy, right? Add the credits. The problem is that there is absolutely no incentive for Spotify or Apple to incorporate credits into their systems. It will be expensive, time-intensive, and difficult. Apple has 60 million songs, Spotify has 50 million. It’s quite a task.

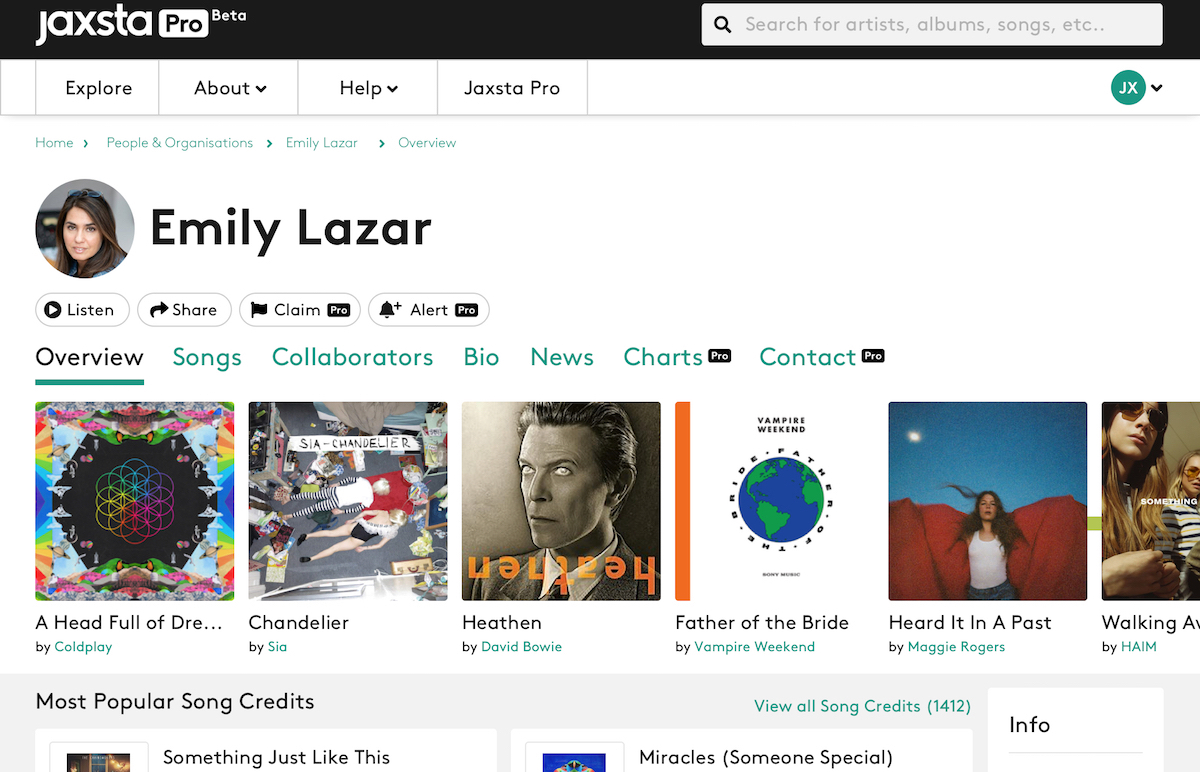

Image: Jaxsta

Jaxsta is an Australian music tech company aiming to plug this gap. Their ad-supported model aims to compile the world’s largest database of album credits. It allows listeners to search individual musicians, producers, engineers and songwriters – and even create alerts if you wish to follow an artist’s career. It’s a good start, but Jaxsta will need to have its database incorporated into the Spotify and Apple Music interface for this to really take off.

I contacted Jacqui Louez Schoorl, CEO and co-founder of Jaxsta. She explained how the company’s goal is “to give credit where credit is due.” They already boast the world’s largest publicly available database of music credits – more than 100 million music credits spread across more than 40 million pages – and all is officially sourced from record labels, not crowd-sourced. This cuts down on possible mistakes.

“As the music industry has become digitised, accurate metadata retention has become a huge problem, one that has ramifications not only for music fans looking to discover new music, but also for professionals working in the industry who rely on their credits to create more opportunities.”

While I had focused on the benefits to consumers, Schoorl points out that artists are often penalised by not being able to easily track their own credits.

“The very notion of having a single official repository for your credits – which is what Jaxsta offers – has incredible benefits for artists, songwriters and other creatives. Songwriters don’t always know when their music has been released, for example. In fact, we’ve heard of cases where songwriters have only learned that their songs were out by looking at their Jaxsta profile – they’ve then notified their publisher, who chased up the royalties. For one of those songwriters, this resulted in them earning several thousand dollars of additional royalties they didn’t even know they were owed. ”

As for Spotify and Apple integration, it sounds likely. Although Schoorl intends for the database to remain 100% independent, she explains that “part of our business plan is definitely launching a suite of ‘Big Data’ solutions that would enable any purchaser, including DSPs, to greatly enhance the user experience.”

Gracenote is probably a word you haven’t thought about for a while, but they solved a similar problem, by inventing an internet-based database that could recognise the content of CDs and deliver metadata based on this. If you can remember the self-inflicted punishment of having to manually type in the title of each song on an 18-track punk record into your iTunes library – then do this hundreds of times a year – you’ll also remember how great it was when Gracenote was incorporated into Winamp and iTunes, and the song and album titles, plus the album artwork magically appeared once you connected to the Internet.

Perhaps none of this matters, except to the music nerd. After all, since at least the ‘90s, television networks have been gracelessly squashing their ending credits into a tiny box and running commercials over the top. Netflix don’t even bother with the pretence, giving you five seconds of tiny-fonted credits before they start the next episode. You can also skip the opening titles too, just to make it clear how little the creators matter.

Musicians have seen the saleable value of their records plummet, but having their names and efforts erased somehow seems like a bigger loss.

No doubt this will be corrected before too long, but at the moment, the artists that make your favourite music are invisible – and it’s a real shame.