What I Learned After Collecting 300+ Vinyl Records

Vinyl records are having a moment, and seemingly not a short-term one. Here, Stefan von Imhof breaks down the value of vinyls when it comes to the music industry, joy, nostalgia, but also, investing.

The Vinyl Revival Continues

There’s no need for me to profess my love for vinyl yet again.

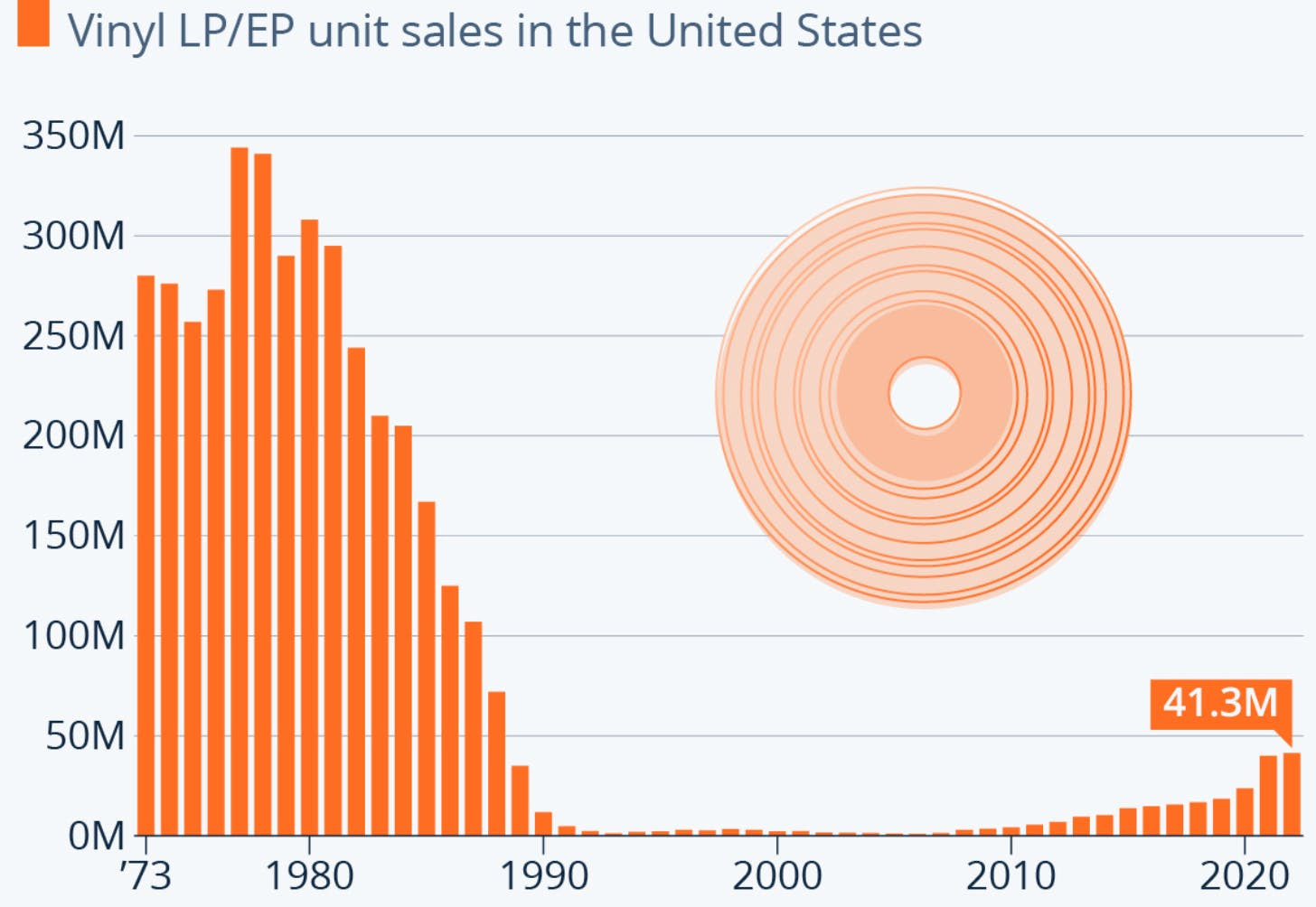

I’ll just say this: I am certainly not the only one who has caught the bug. The vinyl revival is now its 17th year of solid growth.

Vinyl revenue jumped 17.2% YoY, to U.S. $1.2 billion

While 2021 was a bonkers year, 2022 still managed to break new records (pun intended):

- LPs accounted for 43% of physical album sales in the US

- Vinyl records outsold CDs for the first time since 1987

Vinyl anecdotes are through the roof:

- Taylor Swift was responsible for an astonishing 1 in 25 vinyl records sold in the U.S.. She earned almost as much from vinyl, CDs and cassette tapes ($22m) as she did from streaming ($26m)

- In response to supply bottlenecks, Sony and Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab (manufacturer of the world’s best-sounding records) have announced they will open new vinyl factories in Japan and California, respectively

- The ever g̶r̶e̶e̶d̶y̶ smart Metallica has joined in the fun too. They recently bought their old pressing plant, and plan to fully control the supply of their records, top to bottom

- Perhaps most interesting is the data from Luminate which found that half of vinyl buyers don’t even own a record player. Wow

But it’s important to take a step back.

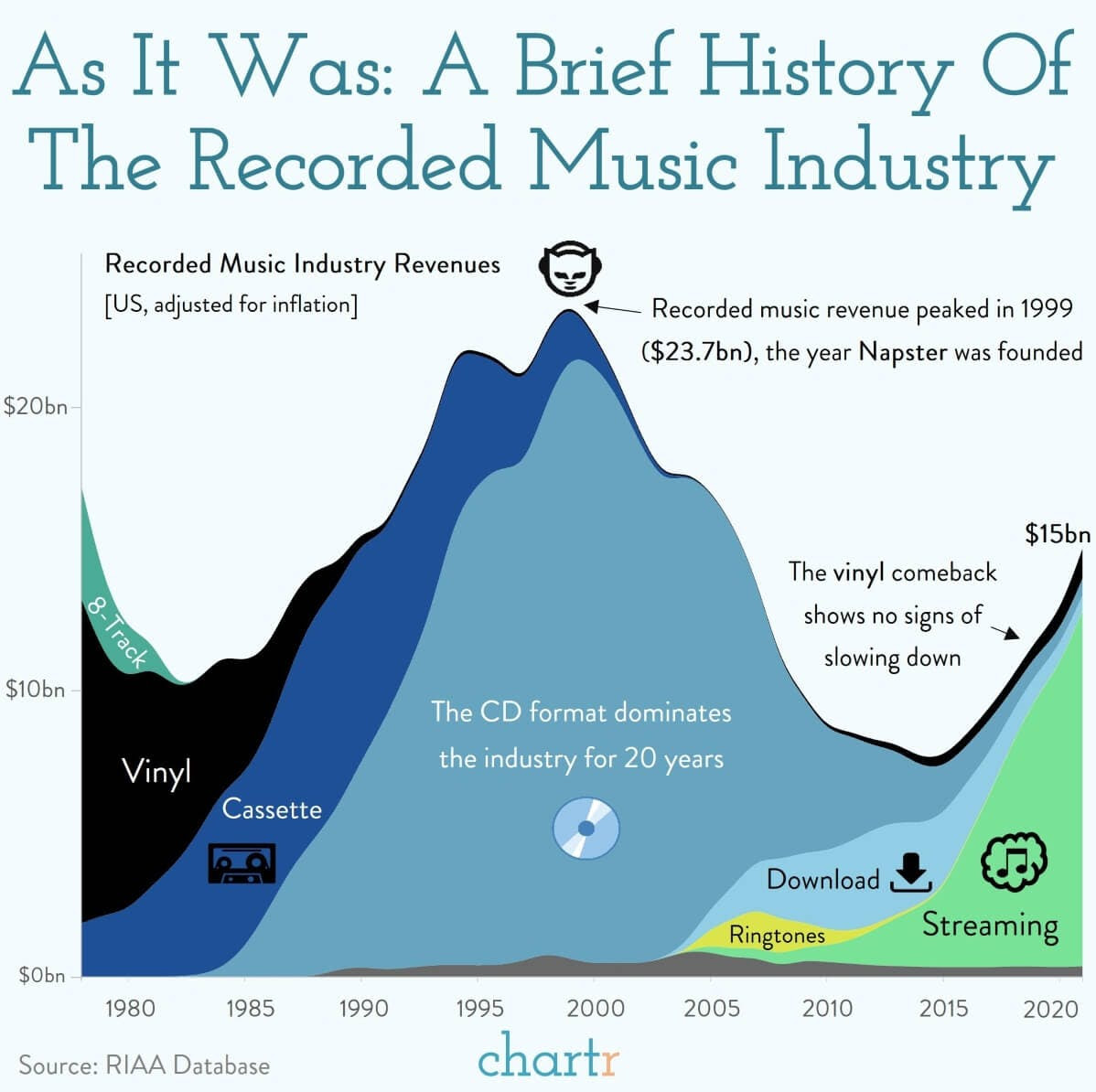

Yes, vinyl was 43% of physical sales last year. But streaming is obviously taking over.

Spotify grew its listeners faster than ever in 2022 (though they are still losing money), and streaming accounted for 90% of all music revenues last year ($13.3 billion).

Vinyl has overtaken CDs, but let’s not kid ourselves; it’s still a rounding error compared to streaming. Graph courtesy of Chartr.

The thing is, nobody makes all that much money from streaming. Not Spotify, not the labels, not the artists. And certainly not you.

But you can definitely make money from vinyl records.

Here’s a bit more about my journey.

300 records don’t take up too much space, but boy is vinyl heavy. Never store vinyl flat. To prevent ringwear, you need store it vertically

What’s the Best Way to Buy Records?

Here are some different ways to buy, and my experience with each one.

Record Stores

If you’re like most people, you haven’t been inside a record store lately. So you probably think records are pretty cheap, right?

After all, it’s not that popular. And we can just stream everything now. How expensive could they be?

My god, you have no idea. Prices are out of control.

Expect to pay U.S.$30 – $60 for new sealed records. $100+ for limited editions, easy. This stuff is no joke. Supply is constrained like crazy, and demand keeps growing.

Look, record stores will always be a huge part of the buying experience. It’s where it all started, and it’s still my favorite. But the fact is, you won’t make money buying new. The best record stores are Meccas for used records. Having new stock is almost secondary.

It’s about the thrill of the hunt. Finding that mispriced, hidden gem just sitting there. Digging through dusty crates for hours until, finally, you strike gold.

From Nigeria to Melbourne: I found this ultra-rare 1978 William Onyeabor album in Fitzroy. The neighbourhood is ground zero for Aussie record collecting. The cover is a mess, so it only cost AU$100. But it plays like a charm, which matters most.

Auctions

Auctions can be a terrific way to buy records.

Boomers bought records like crazy throughout the ’60s and ’70s. As they downsize to smaller homes (and pass on to the next life) they have dozens of records that don’t go with them.

Estate sales are usually chock-full of collections. But you’ll be bidding against other collectors and record store owners, who are all over these like flies on honey.

In my experience, auction lots are usually split one of three ways:

- Batched together by artist. A bunch of Elvis records, a bunch of Led Zeppelin, etc.

- Batched together by genre. Alternative rock, disco, etc.

- Boxes or crates of miscellaneous records

Buying a box full of randoms is always an adventure. Auctioneers don’t always list all the individual records, so you never know exactly what you’ll get.

You can definitely find gold this way. Sometimes a great record is slipped into a sea of bad ones, but the problem is all the junk you’ll get in addition. Vinyl is a heavy pain in the ass to lug around, sell, and ship.

I see Allman Brothers and… *squints* ..is that Johnny Cash? Bidding was worth it for those two records alone. I won this lot for about U.S.$35.

I see Allman Brothers and… *squints* ..is that Johnny Cash? Bidding was worth it for those two records alone. I won this lot for about U.S.$35.

For me, auctions have been the most cost-effective way of acquiring good records at good prices. About half of my records, and nearly all of my biggest “wins” have come from auctions or estate sales.

But I end up giving most of the unsellable crap away to thrift stores.

Shows and Private Sales

Record shows are a great way to both find and make deals.

Most booths are run by record store owners selling their supply. But you can sell and do deals with just about anyone.

Private sales are full of the stuff record stores wish they had. Collections carefully curated over decades, usually in terrific condition. Some of my best records came from this private liquidation sale.

My most valuable record is this Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab pressing of The Beatles’ “Revolver”. I probably overpaid a bit ($250). But on the plus side, it’s the single best-sounding record I own. Like Paul McCartney is in your living room.

Marketplaces

eBay has tons of records, and Amazon often has fantastic sales (if you’re in the U.S.).

But I prefer purpose-built marketplaces. The two best are Whatnot and Discogs.

Whatnot

Whatnot is an online marketplace specialising in collectibles and toys. It’s a platform where buyers and sellers come together to buy and sell items such as Funko Pops, Pokemon cards, and other pop culture items.

What I like about Whatnot is its live events. The platform hosts live auctions where buyers can bid on rare and unique items in real-time.

Whatnot hosts livestream auctions, like this one from Forevervinyl

Discogs

Discogs is my favourite site for buying records, researching prices, and just exploring what’s out there.

It’s the world’s largest record marketplace, and has been around since 1999 (unfortunately the site still feels like it, too). Discogs has millions of richly detailed listings, and is arguably the most important (and trusted) resource for record collectors, DJs, and fans.

Discogs’ UX leaves a lot to be desired. But its database is second to none

My favourite part of Discogs is the collection feature. You can upload your entire collection into the database, and immediately find out what it’s worth.

Discogs makes this very easy. Their barcode scanner is especially handy for checking prices on the fly.

When you see people at record stores whip out their phones, it’s usually to scan the barcode and check recent sales prices on Discogs

It also gives you the sales history of individual records.

Here’s the sales history for a special edition of “Give Up” by The Postal Service.

I bought this record for a bit above the long-term median price (AU$80), but the recent momentum gave me confidence this will hold its value well over time

But to succeed, you’ll need to know which pressing you have.

Identifying a Record Pressing

Finding the exact record you own isn’t usually as easy as scanning a barcode. Boy, I wish it was.

There are often multiple pressings for each record. Pressings are very important to this world. Some pressings sound better than others. Some are famous (or infamous), for one reason or another. Prices for different pressings can vary wildly. So you need to find the exact pressing you have.

The problem is that UPC codes (barcodes) didn’t appear on records until around 1983. So old records don’t have them.

Instead, vinyl collectors are stuck scouring LP sleeves, entering number combinations, making sure labels match the image on the screen, and worst of all, searching for markings on dreaded runout groove – shudder.

What is the runout groove, you ask?

The runout groove (or “matrix” as it’s called) is the small area of a record between the end of the last track and the label. During manufacturing, an employee literally etches a series of numbers (and sometimes hidden messages) into the press, so it shows up on every record.

But they are just barely visible. These etchings are seriously next to impossible to see. You need superhuman vision to figure out what’s etched into the wax. This is like the final boss of record cataloging. Brutal.

The dreaded runout matrix is why a magnifying glass is a must for every collector. Can you see it? Hold your record up to the light and try to have it reflect at just the right angle, all while squinting and trying not to blind yourself from the shine

My Vinyl Portfolio

Even if you don’t plan on selling, uploading your entire collection is a great idea just to understand what you’re sitting on.

I’ve uploaded my collection to Discogs, which shows me the minimum, median, and max sales prices over the past few years. The marketplace is liquid as hell, so I can confidently use Discogs to determine how much my records are worth.

Discogs gives you the minimum, median, and max price. The median is a good baseline for understanding value. Records in VG+ (Very Good Plus) or NM (Near Mint) condition can sell for well over the median

But I treat my record collecting like a serious investment. I don’t just want to get a snapshot of what my collection is worth: I want to know how my collection is trending over time.

A snapshot doesn’t help me much anyways, as I’m constantly adding and reducing “positions”. I know this stuff is valuable in the long run, but I want to ensure I’m buying well.

So I created my own spreadsheet. Each month I export my collection data from Discogs, and enter the amount I spent each that month on records.

With this, I can measure:

- Median cost per record

- Median profit per record

- Median profit margin per record

With this data, I can see that I’m up about 27% over the past year, or about 2% MoM.

But after tracking this for about a year, I’ve come to an obvious but important realisation.

There are two distinct markets here. One matters a lot more than the other.

The High-End is Pulling Away From the Pack

I realised that as far as gains go, my top 30 or so records were responsible for nearly all the appreciation.

My grails, so to speak, are the only pieces in my collection that move the needle. The rest is doing very little for me. It’s not losing money, but it’s just sitting there collecting dust.

And if they’re never getting listened to, then what’s the point? It’s not worth it.

Discogs has realised the same thing. The chart below shows the price of the No. 1 items in the monthly list of 30 most expensive records, and averages them by quarter.

A few things become apparent. The big takeaway is that the highest-priced records are trending way up.

This may seem obvious, but it goes deeper. Before 2017, only one album on Discogs cracked a $5,000 sale price. Since then, the highest-priced records have suddenly and consistently pulled away from the rest.

Top-end prices are at an all-time high, and vinyl is as cool as ever. It’s even led to some fear of vinyl being commodified the same way modern art (arguably) has — functioning purely as a material to be bought and sold by deep-pocketed investors in hopes of selling for a tidy profit down the line.

We’re seeing stratification between the market’s low and high end, and even within the high end itself. I paid the median price for this Beatles album — about AU$300. But the difference between the lowest and highest sale price is nearly eight times

Are CDs the Next Vinyl Records?

As the compact disc celebrates its 40th birthday, the continued strength of the vinyl record market has some wondering if CDs could someday appreciate like vinyl.

There was a funny viral video about this late last year. The mum refuses to get rid of her CDs, because she got rid of her vinyl albums, “and they came back”.

respect this mother pic.twitter.com/iOpTCe0ICu

— BRAD ESPOSITO (@bradesposito) October 25, 2022

The thing is, she’s right. Vinyl was cheap in the early 2000s and extremely expensive now, thanks to millions of collectors like me.

But mathematically, vinyl records and CDs have the same audio fidelity. They’re more durable, too. They don’t scratch, they barely ever skip. They’re smaller, lighter, and easier to store. And they last longer.

I’m not the only one who feels this way. CDs are already far more expensive than you’d think (Don’t believe me? Walk into a record store and check the prices.)

Ableton Live creator Robert Henke says that “it’s time to stop pressing vinyl and fully embrace CDs”.

Don’t throw away your CDs.

Save them all, enjoy them, and thank me in 15 years.

Closing Thoughts

Vinyl record sales may still be far from the glory days. but you don’t need a return to glory days to make this a fascinating market.

Prices are absurd, and the market keeps going up — so much so that famous music writer Ted Gioia argues the industry is scaring would-be buyers off, and killing the golden goose.

People get into records for all sorts of reasons. But what I love most about this market is it’s one of the few collectibles where the asset is expected to be used.

Think about it: If you own a rare baseball card or sealed action figure, there’s not a whole lot you can actually do with it besides stare at it. Sure, it’s a great conversation starter. But you can’t take it out of the package, or you’ll destroy the value.

But vinyl records aren’t expected to be sealed. A blue-chip record with some slight sleeve wear is totally normal. Records are far more than just a mantle piece: It’s expected that collectors actually use and enjoy them.

The most important thing I’ve learned with my collection is to focus on quality over quantity. You can only listen to so many records each day, and the data clearly shows there’s no financial gain to be had from low-end records. I’m less concerned about acquiring my next 300 records than selling off the bottom half of my collection.

I’m not saying stay away from cheap records. They can be fun. I’ve found gold digging through record store bargain bins. I love the hunt.

But just know that from an investment standpoint, the high end is all that matters.

Happy digging.

Stefan von Imhof is the co-founder and CEO of Alts. This article originally appeared on Alts and in his Sunday Edition newsletter. It was reprinted here with permission.

Read more: Jack White calls on major labels to invest in vinyl: ‘We’re all on the same team’