Read an excerpt from Stuart Coupe’s book ‘Roadies – the Secret History of Australian Rock’n’Roll’

Renowned author Stuart Coupe – the writer behind bold portraits of the Australian music industry like The Promoters and Gudinski – has today released his backstage pass to the hidden side of the music industry.

Roadies – the Secret History of Australian Rock’n’Roll, out now via Hachette Australia, pays tribute to the industry’s unsung heroes, whilst taking us behind the road cases to see inside their world of pre and post-show excess.

In the excerpt below, Stuart Coupe tells the story of Tana Douglas, rock’n’roll’s first female roadie. Douglas spent her life travelling on the road with acts from AC/DC and INXS to Elton John and Iggy Pop, The Who and Ozzy Osbourne, traversing every continent from the ’70s through to the new millennium.

Read the full chapter The First Woman below:

The First Woman

Howard Freeman remembers being at a Sunbury Music Festival with Tana Douglas. The memory still makes him smile – and bristle. ‘Someone didn’t want her backstage in the security area and I told them to get fucked,’ he says. ‘That was the first time I got to say the words: “Fuck off – she is a roadie.” For Douglas to get through all that was pretty amazing. She did it by the size of her balls. And she was very good at her gig.’ Tana Douglas can lay a strong claim to being the world’s first female roadie. And not only was she a roadie, she also spent an extended period doing sound for AC/DC. Yes, that’s right. Sound. For. AC/DC. But doing things that hadn’t been done before was what Tana Douglas did best. From the age of nine or ten, Douglas began running away from home and school. Eventually she was put in boarding school, which was harder to run away from. At boarding school in 1969 Douglas heard about the upcoming Woodstock festival and wanted to go. She called her dad and told him she wasn’t coming home for the holidays – she wanted to go and see Janis Joplin sing. She was about eleven at the time. This wasn’t going to happen. Of course, Douglas’s father hopped in his car and drove to the school immediately, thinking his daughter had gone mad. She was too young even to know where Woodstock was. So Douglas and her father had a serious sit-down. She told him that if she could go to Woodstock, she would study hard and get A grades in everything, and she’d never ask for anything ever again. She figured she had to go because it’d be the only chance she’d ever have of seeing Janis. Sadly, she was right about that: Joplin died just a few months after the festival. Eventually, Douglas did a runner and made her way to Nimbin, in northern New South Wales – ‘Australia’s answer to Woodstock’, as she calls it, ‘for everyone else who felt ripped off by not being able to go’. Soon Douglas was doing the whole hippie thing. In 1973 in Nimbin she met a French guy called Philippe Petit, who a year later would walk across a tightrope between the two World Trade Center buildings in New York City. In Nimbin he and a coterie of friends were planning a less ambitious but still audacious venture. Petit was intending to do a tightrope walk between the northern pylons of the Sydney Harbour Bridge – just for practice, to get into the swing of things before tackling the World Trade Center. To Douglas, this seemed beyond exciting, so instead of staying in the rainforests and growing pot she joined Petit’s gang and headed to Sydney, where she had a small but important role in the walk. ‘I didn’t do any of the rigging because obviously that’s really technical and they had their own crew for that,’ she recalls. ‘I was part of the ground crew – one of the people who caught the cans of film as they dropped them down off the edge and then took off like I was in The Great Escape so they didn’t get confiscated.’

After the thrill of the bridge walk, Douglas left Sydney and headed to Kuranda, growing pot and settling into the hippie lifestyle once again, but the lure of Sydney was strong and she soon returned. ‘I’d been running around naked pretty much, in the forest. It was the whole “Kumbaya” thing up there, playing guitar by the fire every night looking at the stars thing up there,’ she says. ‘Everyone was telling me not to go back to Sydney, and certainly not to Kings Cross, but by now I was curious and my response was: “Why not?” So, off I went.’ By chance, Douglas ended up sharing an apartment with two other young women who were into the Sydney nightlife. They started club-hopping together, and it was at the Whiskey A Go Go in William Street, just down from the main drag of Kings Cross, that Douglas met a man who would play a major role in her life: the already legendary Wayne ‘Swampy’ Jarvis. ‘He was working with some R&B band from the States playing for all the American soldiers. It was really the dregs of that scene, with lots of servicemen coming through. But I was pretty interested as the music was completely electric, whereas in the forest where I came from it was all acoustic. I was asking Swampy questions and he was telling me things, and then he asked if I wanted to come back the next night, which I did.’ Douglas rocked up late. Everyone involved with the band and the show had gone out and got trashed the night before. The gear was staying at the club for the next night’s show, so there was no packing up and loading out to do. Party time. That was why the sound guy figured he could arrive at the very last minute, along with the band – but the cleaning ladies at the venue had thought they’d do the right thing and clean his desk for him, so all the settings had been changed from the way he left it. When Douglas arrived the guy was freaking out, running backwards and forwards between his desk and the band and trying to get everything back the way it was.

‘Swampy’s running around too,’ Douglas remembers. ‘I asked what happened and he said, “The fucking sound guy isn’t happening – that’s what happened!” The show that night was terrible, and I only stayed to see if he could get it together in time.’ The next day Swampy and the band were heading to Melbourne. Douglas was amazed that people actually got paid to travel with bands. Not long afterwards, one of the women Douglas was sharing her flat with said that some friends of hers from a Melbourne band, Fox, were coming to Sydney for some gigs. This flatmate was driving Douglas crazy, forever carrying on about how great Melbourne was, and how her parents would take care of her if she moved back. Douglas started praying that Fox would give her flatmate a lift back down south. At their last Sydney gig of that run she introduced the idea to the band’s guitarist, Peter Laffey, who said that if all the band’s gear was packed and they got on the road that night, the flatmate could come with them. Now Douglas was on a mission. ‘I looked at the stage and all the gear, and everyone was wandering around in circles and doing nothing, so I offered to help. Everyone in the band laughed, knowing the reaction I’d get from their crew guys, so I wandered over to the stage and told them I’d give them a hand and asked what I could do. They showed me how to coil cables. There is a definite way to do it correctly and I learnt how.’ As Douglas worked, the other roadies started picking up their game: they didn’t want to be shown up by some girl. In no time they had everything loaded into the truck. Douglas threw her flatmate into the front seat, and off she went. The next time Fox returned to Sydney for more gigs, they called Douglas and said they were a guy short: did she want to come and do the gig? It was that casual. She thought it was hilarious that they asked, and figured they just wanted to see if she could do it again.

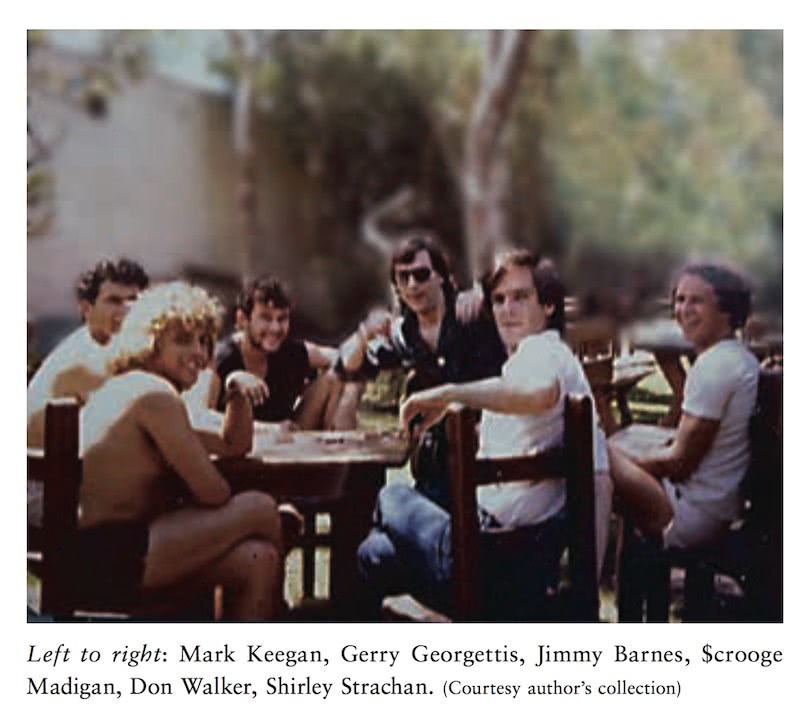

During Fox’s run of Sydney shows, Douglas met a roadie who would mentor her: the already established, already bordering on legendary, and certainly infamous $crooge Madigan. He was the roadie for Daddy Cool, with whom Fox was doing a show. Swampy Jarvis was also at the gig as he was working for the promoter. These guys took Douglas seriously. ‘No one acted like, “What the fuck is going on?” – they just told me what went where, and I just went and did it. I was just sponging everything up, and I didn’t want to make a fool of myself. Then Fox said they were going back to Melbourne and asked if I wanted to go back with them.’ Fox’s booking agent worked in what was known at the time as Mushroom House, and that was where Douglas met a young Michael Gudinski. She went to the office every week to collect Fox’s worksheets, which explained the details of the gigs they had coming up. Fox was doing okay for a band of their level, with three or four shows a week in and around Melbourne. Douglas thought that was a lot – until she saw the work schedule of the next band she would get involved with. The roadie world at this time was still comparatively small. There was $crooge, Swampy, John D’Arcy and a handful of others. They all knew each other and knew the lifestyle. They were all blokes until Douglas came along. And because she was accepted by the ‘cool guys’, other roadies accepted her as well. Fox began to run out of steam, so booking agent Bill Joseph started to look around for other work for Douglas. Joseph became a father figure to her. ‘He was kind, always letting me into his office and telling me things and teaching me stuff,’ she says. ‘Gudinski would fly in and out of rooms and I’d listen to what I could from him, too. I think everyone got used to me just being around. It’s like a stray kitten that wanders in and someone feeds it, and before you know it everyone’s feeding it. Then it’s, “Oh yeah, that’s our cat.”’

Stuart Coupe, Courtesy Susan Lynch

One day Joseph mentioned to Douglas that there was a band coming to town and they’d be looking for a full crew, and he thought it’d be an interesting job. Douglas felt loyal to the Fox guys but still she didn’t really hesitate. It was definitely interesting – and more. The band was called AC/DC. Joseph hooked Douglas up with their manager, Michael Browning, and she went round to the band’s house in Lansdowne Road, East St Kilda. It was late 1974. There she met Bon Scott, and Angus and Malcolm Young. Also there were Harry Vanda and George Young. After the introductions were made, they told Douglas the band needed someone to be their stage roadie, and asked if she wanted to do it. ‘I can do that,’ she replied. They also needed a PA, so Douglas went and picked it up. She was thereafter in charge of looking after it. Initially, Douglas was AC/DC’s roadie. There was a lot of equipment that needed moving around. The only person who had more equipment was Billy Thorpe. ‘In the beginning we had an amazing couple of months just hanging around the house, auditioning people,’ Douglas says. ‘They were writing songs and also recording. They’d take off for a couple of days and go to Sydney to record some things, and then they’d come back down to Melbourne. George and Harry would trade bass or drum parts. And that’s how it was. It wasn’t really a band then.’ In Douglas’s opinion, the AC/DC the world knows started at that time in the house in St Kilda. The glam rock period – when they dressed in pink satin and Dave Evans fronted the band – was over. Bon Scott was singing, and the dress – with the exception of Angus’s perennial schoolboy outfit – was workingclass and ‘rock’.

‘They’d been in Sydney, and George and Harry had had the “You know what, this isn’t going to work” chat. That’s when they decided on the change of direction. The big vision started at Lansdowne Road.’

Douglas was AC/DC’s roadie for their first shows with Bon Scott fronting the band.

Buy Roadies – the Secret History of Australian Rock’n’Roll here.

This article originally appeared on The Industry Observer, which is now part of The Music Network.