Read an excerpt from Andrew Stafford’s book ‘Something To Believe In’

Mark this day in history as the day beloved writer and journalist Andrew Stafford released his second future bestseller.

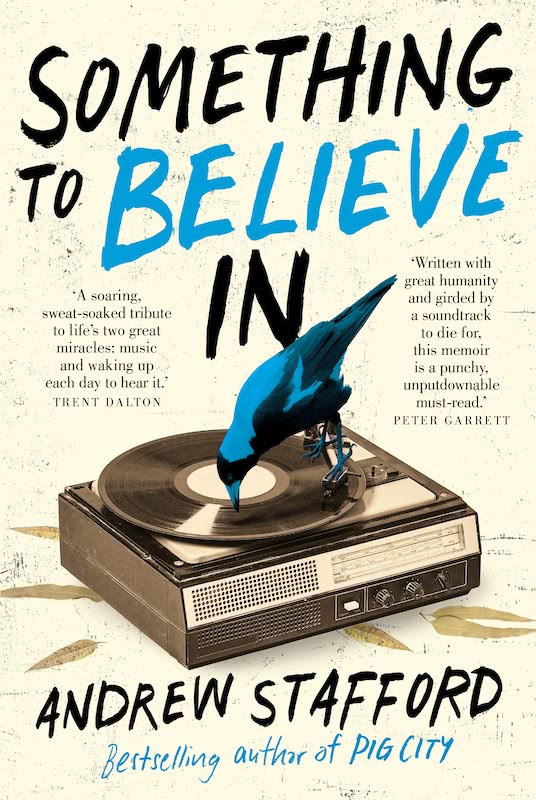

From the author of now cult classic Pig City: From The Saints To Savage Garden comes Something To Believe In, a book for anyone whose life has been saved by rock ‘n’ roll.

Out today via UQP, Something To Believe In is part-memoir, part-rock/gonzo journalism, part pop culture narrative, part-love story.

Midnight Oil’s Peter Garrett called the book “a punchy, unputdownable must-read.”

Lindy Morrison of The Go-Betweens said: “Andrew Stafford takes us on an exhilarating ride through his life as birdwatcher, cab driver, roadie, son, lover and writer.”

While Myf Warhurst said it reminded her of “how much music helps us navigate through life, in all its complicated glory.”

Something To Believe In

Andrew Stafford has bared his soul and his most telling anecdotes to connect with the reader on multiple levels. It’s written for all of us, no matter what point of music fandom we’re currently in.

To celebrate the release of Something To Believe In, we’ve published the full chapter (We Are) The Road Crew on Motörhead below:

(We Are) The Road Crew

You’re probably wondering what happened on the rest of the Euro Double-Vision tour, between Amsterdam and Le Havre, and what happened to the planned book. I tried to write it. There were lots of stories and I wrote plenty of them down – that is, before we actually got on the road. All that dialogue from Amsterdam? I was sitting there taking notes. I couldn’t capture that sort of repartee once I was behind the wheel and, as I said earlier, you really can’t make that shit up. Not me, anyway.

For the first few days of the tour, through the Netherlands and Belgium, we had a Peugeot seven-seater which wasn’t big enough to easily accommodate the gear. It ended up sitting on top of the band. They were up to their eyeballs in luggage and equipment and I had to ask Andy, on my right, to check the mirrors every time we changed lanes, because I couldn’t see them. And we had to change lanes often, especially on the autobahns, where I got used to driving at 160 kilometres per hour, only to have to get out of the way of lunatics barrelling past at 200-plus.

In Caen, France, we picked up a Volkswagen Crafter, a dual cab with ample space for gear in the back. Someone stunk it out for days with a hidden wheel of Gruyère cheese until Gregor finally found it and binned it in disgust. I’d driven ten- and eleven-seater vans at home, but the Crafter was a significantly bigger vehicle in all dimensions, and difficult to manoeuvre through the jammed, narrow backstreets of Paris and Marseilles. I was also steering a left-hand drive manual vehicle on the right-hand side of the road for the first time. I adapted reasonably well, but there were anxious moments and we nearly came to grief in Paris.

Andrew Stafford

Stooges drummer Scott ‘Rock Action’ Asheton once nearly scalped his band when he drove their twelve-foot truck under the ten-foot Washington Street Bridge in their home town of Ann Arbor, Michigan, peeling back the top like a sardine tin. The same fate nearly befell us when we found ourselves in the wrong lane driving along the Seine and approaching a tunnel for which the Crafter was over-height. Drastic rock action was needed and I jumped a couple of lanes and out of trouble with seconds to spare. When we made it to the venue I had a cigarette, and I don’t smoke. After the show, someone tipped a beer keg on my foot. It emerged swollen but not broken, and I kept driving.

There are hundreds of songs about touring. I understand why. It’s both a bonding experience for those involved and a warped one: distorted by intoxicants, language barriers, cities you glimpse, faces you’ll never forget but will never see again, new friends that too rarely become old ones and, especially, fatigue. One telling memory comes from Valence, in southern France. We found a park for the Crafter just around the corner from the night’s venue. There was a roller-door grille out front and – with my back to it – I slid down and passed out on the spot.

(We Are) The Road Crew, by Motörhead, captures this madness-inducing grind as seen by the drivers, luggers, lifters and loaders. That makes it far more pungent and convincing than almost any road song sung from the comparatively lofty perch of a musician, and it is pure, foot-to-the-floor rock & roll. A big part of the band’s sound was the double-kick drive provided by drummer Phil ‘Philthy Animal’Taylor. That barrage of kick drumming forms the eighteen wheels this semi-trailer of a song runs downhill on; Taylor’s snare shots sound like cars being passed.

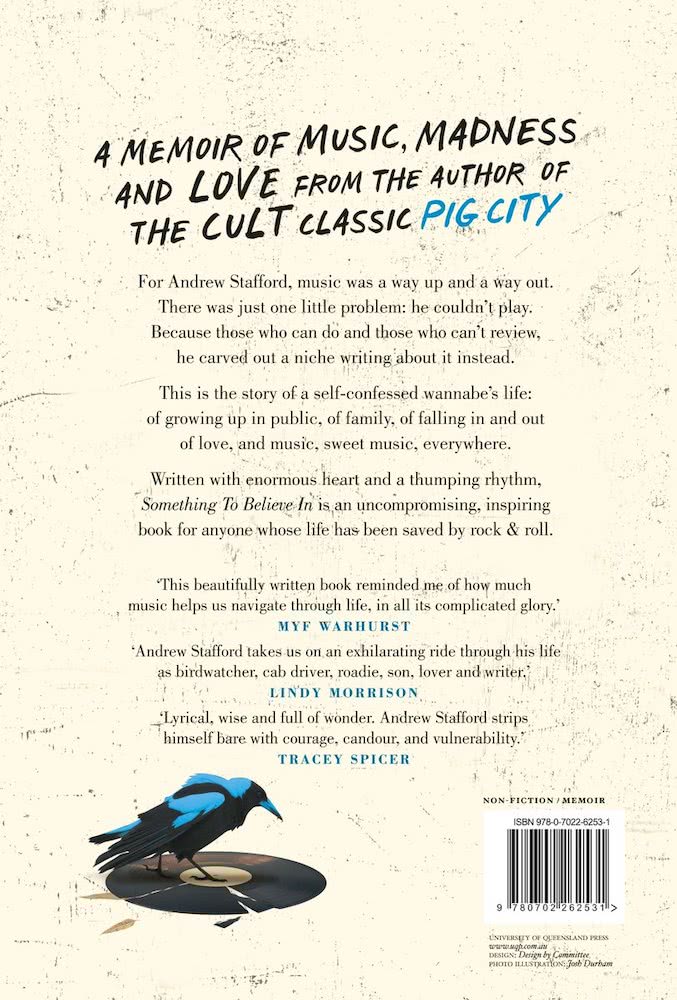

Something to Believe In – back cover

Musically, there’s not a lot to it – it’s all power, speed and volume. Each twelve-bar line is delivered by Lemmy with a voice like an iron fist held aloft. ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke accompanies him on an A chord before two bars each in G and E, followed by the triumphant rallying cry of the title, then a simple guitar lick.

The song is just over three minutes – long enough to make its point and no more, though theoretically, like the road, it could go on forever. In between, Clarke roars through two solos, the first no more than twenty seconds long, before another two verses, the title again, and another, longer solo that drives the semi-trailer over the cliff with murderous intent.

It’s often said that Motörhead helped pioneer thrash metal with that double-kick drum sound. It’s possible they did, but I don’t blame them for it, because they had nothing else in common with the genre’s big four (Anthrax, Metallica, Megadeth and Slayer). Lemmy always said that, like AC/DC, they were a rock & roll band – nothing more and absolutely nothing less. They had more in common with punk, especially the Ramones, for whom they wrote a tribute song so perfect – R.A.M.O.N.E.S. – that the Ramones ended up covering it themselves. Like the Ramones, Motörhead defined their sound and image early, rarely deviating from it thereafter.

Motörhead were far heavier, though, even if they weren’t quite heavy metal. Their motto was ‘everything louder than everything else’: Lemmy, who had a way with one-liners, once said they were so loud that if they moved in next door to you, your lawn would die. He was one of the finest lyricists in hard rock, comparable to Bon Scott in his wit, economy and wicked double entendres, and arguably to Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott for his occasional flights of real poetic flair.

Almost every line of the song starts with the word ‘another’. It’s a flash of genius that captures the essential element of road life: repetition. The routine and boredom shatters the illusion of adventure. Lemmy checks off a list – maps, customs, hotels, new words, new scars, alcoholism, junk food, hard labour, loneliness. And there’s no baying crowd, no glory for the crew at the end of the night. Just another stage to pack down and load out.

In 2015, Australian non-profit organisation Entertainment Assist commissioned Victoria University to survey almost 3000 figures in the music industry. It reported staggeringly high rates of mental illness, with roadies faring particularly badly. Low pay, alcohol and drug addiction, poor diet and lack of sleep were all factors. Throw in the difficulties of maintaining relationships and family bonds and you have a cocktail for depression, anxiety, break- downs, rehab and suicide.

Not that those on stage fare much better. Of the lineup that recorded (We Are) The Road Crew and its classic parent album, Ace Of Spades, the colourful Phil Taylor was the first to go, on 11 November 2015, aged sixty-one. Taylor’s death had been rumoured so often that he, along with the Who’s Keith Moon, might have been the inspiration for Spinal Tap’s revolving stool of spontaneously combusting drummers. Liver failure was cited as the cause. Pneumonia got Fast Eddie Clarke a few years later, on 10 January 2018.

‘It’s a shame, man,’ Lemmy told Classic Rock after Taylor’s death. ‘I think this rock & roll business might be bad for the human life.’ It turned out he had just seven weeks to live himself, but in truth he must have been one of the luckiest rock & rollers ever to make it to seventy. Aggressive prostate cancer took him out on 28 December 2015, after he’d lived his entire speed-addled life like a semi-trailer plunging into a ravine.

Buy Something To Believe In here

This article originally appeared on The Industry Observer, which is now part of The Music Network.