How do we fix the singles chart?

With Ed Sheeran’s entire 16-song album landing in this week’s Top 40 singles chart in Australia, it’s time for a rethink.

In American baseball, the ‘90s is known retrospectively as the steroid era, such was the proliferation of players doping at the time. Not surprisingly, this super-human strength resulted in numerous records being broken, as enhanced players smashed their ways to amazing statistical feats. This was great for audiences, who were suddenly seeing balls bashed into parking lots, but it was a nightmare for the statisticians and analysts, who suddenly found their grading curve destroyed.

It was now impossible to compare players from different eras, without taking into account the massive boost certain players illegally gained. Many records that were broken in that era still stand, with mere un-juiced humans proving unable to touch them. All the statistics were now irrelevant. Baseball was forever tainted. Plus, it was pretty boring to begin with…

This is what is happening with singles charts around the world right now. The ability to release music digitally through platforms such as iTunes, and Spotify may have ushered in an era of democratised distribution, but in a sea of endless tunes, it is still — by and large — the old promotional machines put in place by major labels years ago, with their superior man-hours, higher budgets, and networks of radio, media, and television contacts, that end up breaking through. Obviously there are viral hits, regional success stories, and the odd chart-topper from out of left field, but the advantages and exposure granted to artists on larger labels remains much the same.

This week Ed Sheeran’s Divide landed 16 songs in the top 40 of the ARIA Singles chart, with nine hitting the top 20. This is a momentous feat, let’s not downplay that. But how do we compare it to the success of – let’s say Michael Jackson’s singles from Thriller? That album landed seven singles in the top ten in the U.S. while shifting 33 million copies in its own right. This was in an era when black artists – prior to Jackson’s success – weren’t play listed by MTV. It was also an era where single releases were spread across years. The singles from Thriller were released between October 18, 1982, and January 23, 1984. Jackson’s follow-up album spawned five number one singles – a record not equalled until Katy Perry’s Teenage Dream landed its fifth #1 in June, 2011 (an album which was no doubt aided by digital distribution, but still enjoyed a tradition single rollout across nearly two-and-a-half years.)

The closest thing to what we are seeing this week happened way back in April 1964, when The Beatles held the top five spots on the U.S. chart. The band hit America over a year after they first experienced massive success in the U.K. and, due to this lag, their American label Capitol made up for lost time by issuing their entire back catalogue of singles. The (separate) American label who owned the U.S. rights to The Beatles’ first album also issued seven singles simultaneously, and the resulting rush of product saw the band flood the top five, with seven other singles hitting the top 100 in the same week. There were even two Beatles-based novelty singles in the chart: ‘We Love You Beatles’ by the Carefrees and ‘A Letter to the Beatles’ by the Four Preps. It’s safe to assume neither of these are very good.

Any era in which the Pink Panther theme charted was indeed a golden one.

The main difference between this week and the above examples is that they were tied to physical production, and distribution. This prohibitive cost — in money and manpower — stemmed a Sheeran-type flood happening in the past. Not to mention the cost to the consumer, who would be unlikely to purchase 16 different Ed Sheeran singles. What we are seeing now is actually massive album success being reflected on the singles chart, which is and should be a separate thing. When bonus tracks are charting, it’s time to revise.

There are other considerations. What will the single promotion roll out for Sheeran look like now that every single song, including bonus tracks, have entered charts worldwide? More to the point, will labels start avoiding single releases in weeks in which it appears inevitable that an artist of Sheeran’s status – we’re talking Adele, Taylor Swift, Bieber; possibly Rihanna, possibly Beyonce – have an album scheduled for release? Are we going to see weeks in which the singles charts merely mirror the top of the albums charts: like a Spotify shuffle mix of the top five selling albums with the odd big-hitting single and novelty tune thrown in for measure? These established artists crowding out the charts with multiple entries will no doubt hamper the possible success of slow-burning songs which – in the past – might have gradually climbed the lower reaches of the chart, receiving attention and radio play which then magnified sales, leading to further increases in radio play, and so on and so on.

One quick fix could be imposing a limit to how many singles from an artist are eligible to enter the singles chart at any given time. Labels would have to nominate these, and in the case of unexpected viral success, the first, let’s say, three songs to reach the chart will block others from entering, until/unless the artist or label nominates its chosen singles.

That way labels can control which songs are deemed ‘singles’, and can ‘delete’ any singles which are blocking the success of their next, much like a label would have done when gearing up for their second or third single release in the days of physical charts and limited radio airtime. Warner UK deleted Gnarls Barkley’s ‘Crazy’ after six weeks at #1 in order to protect the song from overexposure, which would have killed the album’s trajectory. The same decision was made by Wet Wet Wet after their monster hit ‘Love Is All Around’ begun to get banned by radio stations fed up with the song’s chart success.

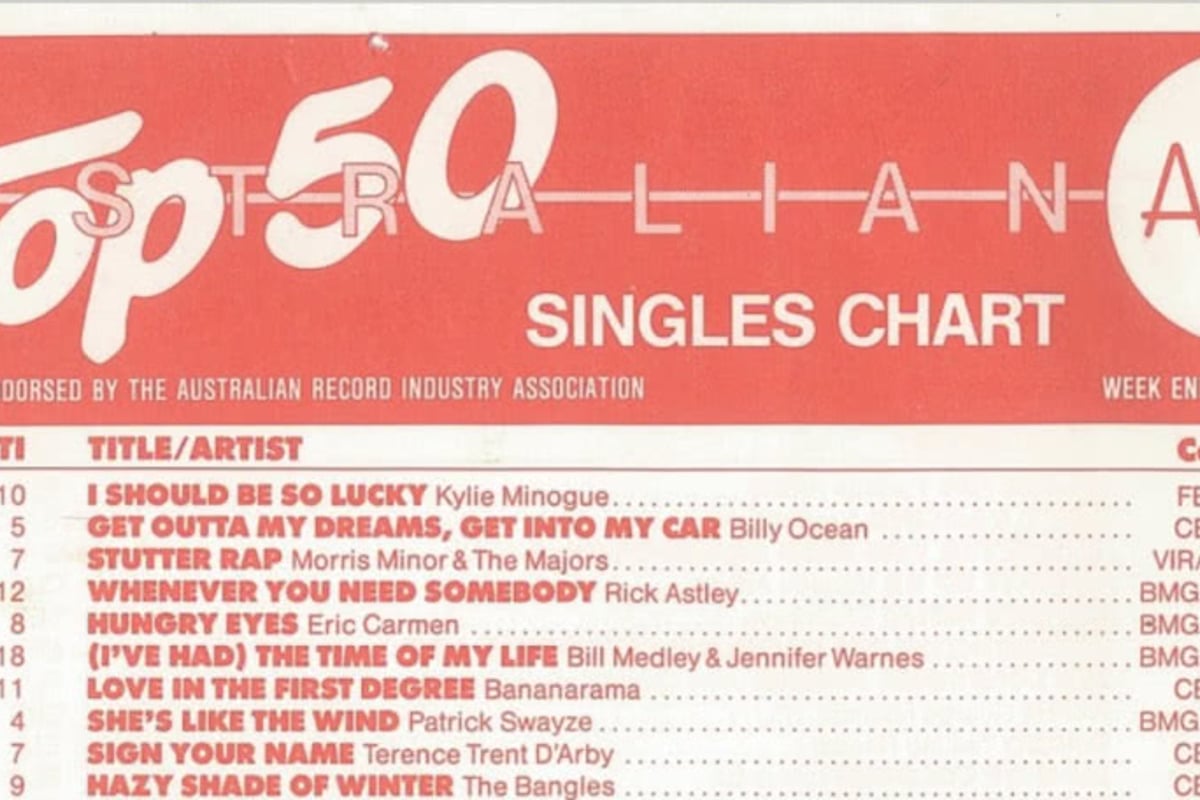

You could argue that imposing such restrictions would mean the charts aren’t a true reflection of which songs are selling, but with streaming included in the make-up of the chart figures from November 2014 in Australia, plus the entire way in which we access music having forever shifted, this point is surely a moot one. The charts today bear no resemblance to the one in the header picture. New controls are necessary if we want the singles chart to retain any relevance at all. It should be a barometer for hit singles, not a reflection of strong first-week album sales.

Ed Sheeran is only the beginning of this.

This article originally appeared on The Industry Observer, which is now part of The Music Network.