Excerpt: Live Wire, a memoir about AC/DC’s Bon Scott

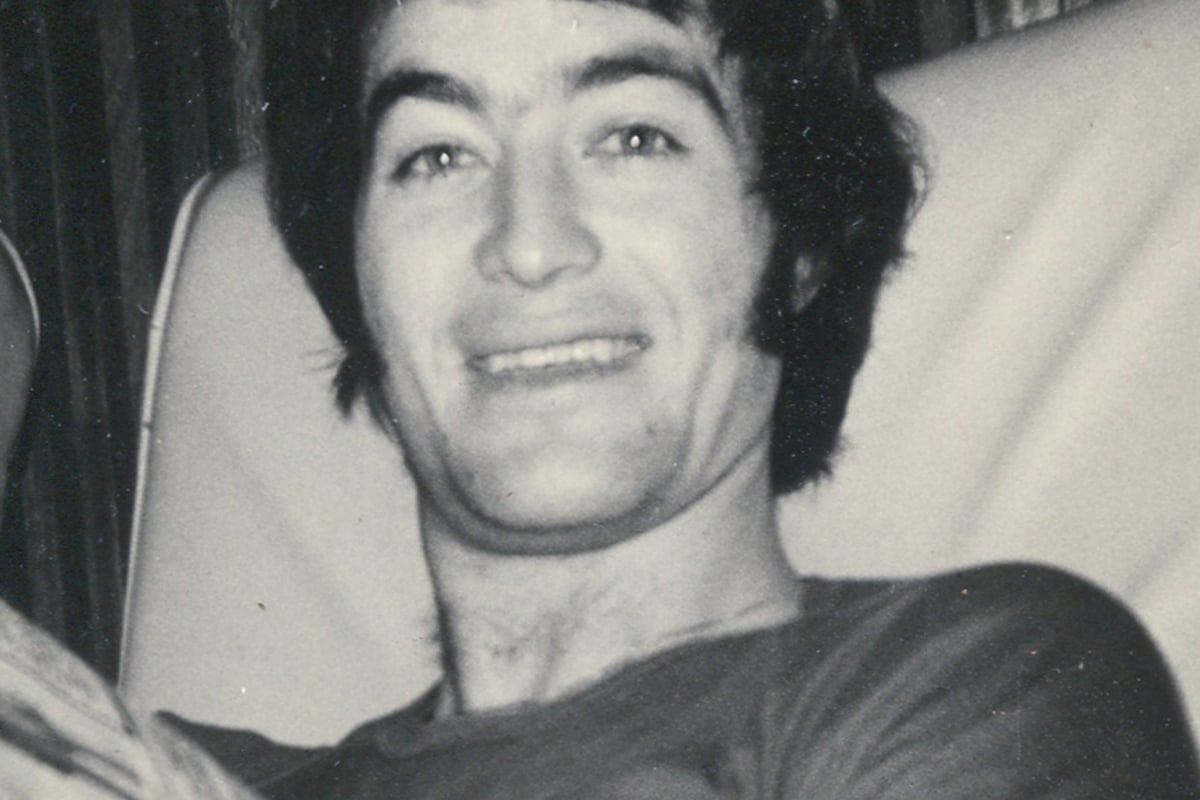

This month, the three people who knew Bon Scott best, his soul mate Mary Renshaw and his best friends Gabby and John Darcy, release Live Wire, the most affectionate recount of the late AC/DC singer’sstoried life and career yet.

Courtesy of the tome’s publisher Allen & Unwin, TMN has published the foreword by Mushroom Group’s Michael Gudinski, and the chapter titled Living The Dream, detailing his years with AC/DC.

Foreword

By Michael Gudinski

It’s funny, before I even knew that Darce, Gab and Mary were putting together this book, I’d been thinking a lot about Bon Scott.

It’s stating the obvious to say that Bon was a figure of inf luence. It’s amazing the number of international acts, all of different generations, that I bring in to tour Australia who want to go over to Fremantle while they’re here to pay homage to Bon. And with the amount of travelling that I do, I’ve seen the ‘Cult of Bon’ develop and grow over the years, particularly in Europe and the States. Perhaps even more so than here in Australia—and we love the bloke!

What a lot of people don’t know is how hugely important Bon has been to me personally. And not the denim-clad, wild-eyed Bon we all know from AC/DC, but the teenybopper- focused co-lead singer of The Valentines in the late sixties. This Bon wore orange frilly shirts and sang ‘bubblegum’ pop tunes like ‘My Old Man’s A Groovy Old Man’, which is bizarrewhen you think about it. Mind you, though, his eyes couldstill get pretty wild.

As a kid around Caulfield I’d already started putting on a few dances—it was easiest during school holidays—and I ended up working for Bill Joseph, who was the manager of The Valentines. Bill was one of Melbourne’s leading promoters at the time and he had a couple of nightclubs as well, and he took me under his wing.

I was pretty green, had never seen any of the rock’n’roll lifestyle—I was still a virgin and had never seen drugs. I was a clean-cut, straight-down-the-line sort of kid.

The Valentines were scheduled to tour Adelaide and I decided to tag along to get an idea of what actually happened on the road. It wasn’t that hard to get permission—I’d already dropped out of school and been kicked out of home. Nothing could’ve prepared me for what ensued, though—that first taste of the rock’n’roll life.

Let’s just say it opened my eyes.

I can’t remember how we actually got to Adelaide but I do recall having to come home on a bus with the band—whatever the local equivalent of Greyhound buses was at the time. I wasn’t a fan of a road trip at the best of times, and going all the way from Adelaide to Melbourne with a bunch of long- haired yahoos like The Valentines was certainly a colourful and testing time. I wouldn’t say it was a particular highlight, but it left an indelible mark. We stayed at the Powell’s Court Motel, in Adelaide, which would become well known as a place for bands to stay in years to come. I will never forget one night when Bon, after spending some time with a particularly enthusiastic groupie, showed me his bed sheets and startedcracking jokes so impressively off colour that I can’t bring myself to repeat them now.I don’t think I’ve been the same since.

There’s no way I would’ve signed The Valentines if I’d had Mushroom Records in the late sixties. They were good, but a product of their time, pumping out bubblegum pop to screaming teenage girls. Ultimately, Bon got sick of the lightweight pop stuff and joined Fraternity, which was a band I really did like. They were a ‘serious musician’s’ group, and gave Bon the cred he needed for the Young brothers to take notice.

I put Bon up as one of the most important music figures this country has produced. If not for a stupid tragedy, he would’ve hit the heights of another tragic figure—Michael Hutchence. To continue the theme, he would’ve been Australia’s Jim Morrison.

Bon’s death was devastating. He and I had kept in touch through the years as both our lives started to blow up. ‘My, haven’t you done well for yourself,’ Bon would joke. To him, I was still the sixteen-year-old kid he tried to get to smoke hash on a trip to Adelaide—and shock with his bed sheets. For the record, I never succumbed to his inf luence and didn’t muck up for the entire tour. Bon had a spirit that f lowed onto the people he was with and I always enjoyed catching up, even if it did used to leave me a little worse for wear.

One thing I’ll never forget about Bon is that cheeky glint in his eye. He could be cocky and a little pushy in his pursuit of a good time, but never aggressive. People seemed to get the wrong impression with the whole denim-vest-and-tattoos thing during the early AC/DC era.

Bon was simply a really decent bloke. He was a ‘bloke’s bloke’, he liked to party, have fun, pull pranks, and he hadthis amazingly powerful voice. There was a song he’d writtenin The Valentines called ‘Juliette’, and if you listen back to it you can hear—behind all the orange and the frills—the voice that was the key factor in what would take AC/DC from what they were before, to what they would become.

I actually live not too far from where The Valentines shared a flat on Toorak Road in South Yarra, and I still think about Bon and those days when I drive by. Music is big business nowadays, but back then it was a different world. It was liber- ated and free: dictated by energy and adventure rather than commerce. The usual deal was one band, one roadie and three gigs a day, and a real sense of camaraderie built up around the group and the little community around it—people like Darce, Gab and Mary. I’ve bailed Darce out of jail, given him and Gab a place to have their wedding, and an old business partner of mine managed Mary’s brother’s band. At one stage we all had neighbouring shops in Greville Street, Prahran. These are the people and the times that informed a lot of my early life decisions. If I hadn’t taken a four- or five-day trip to Adelaide I might never have got into the music business. That’s how important Bon and these other guys are to me, so you can understand why I still think about them a bit.

It’s great that Mary, Gab and Darce are now sharing their memories of a unique time in Australian music and a very special bloke. I hope you enjoy them, they mean a lot to me.

Darce

The first time I saw Bon singing with AC/DC was at a gig in Sydney at the end of 1974. Bon was wearing bright satin overalls with a little bib’n’brace. He had nothing on underneath and his balls were hanging out. It wasn’t a great look, but I knew that musically he’d found his home. I thought Fraternity was a good band, but this was a great band.

I was buzzing when I caught up with Bon after the show.

‘Fuck, mate, that’s the best I’ve seen you fire up.’

‘Yeah,’ Bon replied, ‘I’ve got these young dudes behind me, kicking me in the arse, and I feel great.’

‘Not too sure about the pink overalls, though,’ I laughed. It was great seeing Bon front a no-frills rock’n’roll band.

He was reborn. Just a microphone in hand, backed by some killer riffs.

By this time, I was doing some pretty big gigs, too, working for the promoter Paul Dainty on tours such as Leo Sayer, Bad Company and Joe Cocker. We were doing big shows all over the country, but it was the same old story—setting up, packingup, driving, not getting much sleep. At least we were staying

at better hotels, so the food was good. But we didn’t care how far we had to drive, as long as the gig was good.

Bon stayed with us in Brighton when he came to Melbourne with AC/DC at the end of 1974, and he brought drummer Phil Rudd with him. Phil slept in the dining room; Bon had a room out the back.

On another trip, we saw AC/DC at Festival Hall, which was a big gig for the band. Bon had organised the tickets and we were about four rows from the front, smack in the middle. We were probably the oldest people in the crowd—I was twenty-five and Gab was twenty—and everyone else was going absolutely nuts. I remember Bon was singing when he spotted us. ‘Come on, Darce,’ he yelled. ‘Get into it!’

Gab and I were so grown up we even had a Holden station wagon. After one AC/DC gig, we took Bon, Malcolm and Angus out for a night on the town. We drove to the Chevron on St Kilda Road, with Angus eating a Mars Bar and drinking a milkshake in the back seat. Angus seemingly lived on milk and chocolate bars. Unfortunately, our friend Nicky Pappas wasn’t on the door that night and the bouncer wouldn’t let us in because Angus and Malcolm were too young and Gab was wearing sneakers. I was the only one who would have been permitted to enter because I was wearing a lovely pair of corduroy pants.

So, we took the guys back to their hotel, the ChateauCommodore on Lonsdale Street. That was our big night out!

All the hard yards Bon put in during his Valentines days paid off in AC/DC. He was match-fit. He outlined AC/DC’s punishing schedule in an interview in 1979: ‘We would playour first gig at lunchtime in a school. After that, we’d bringour gear to a nearby pub to play two sets in the afternoon, and finish off by doing two sets at another club. That was the price to pay.’

It was The Valentines days all over again. Except this time, Bon didn’t have to share the vocal duties. He was front and centre, and you could tell he was playing the music he truly loved.

Things happened quickly for Bon and AC/DC. Bon did four years with The Valentines and they never released an album; four months after he joined AC/DC, they released their debut album, High Voltage. Gab and I were living at Monbulk then, which was about an hour out of town, but Bon and his brother, Graeme, came to see us. Bon wanted to personally give us a copy of the album. He was so proud.

Soon after AC/DC released High Voltage, they got a newbass player—Melbourne’s Mark Evans. Bon wasn’t at Mark’s audition. In fact, he didn’t meet Mark until five minutes before his first gig with the band, at the Waltzing Matilda Hotel in Springvale, but they became great mates. And Mark had a lovely description of Bon: ‘What a character that guy was. By his own admission, he was a great bunch of guys.’

Mark also tells a wicked story about a bender with Bon in Paris. Surveying the scene from the tiny balcony at their hotel, Mark remarked, ‘How good is this?’ When Bon didn’t answer, Mark inquired, ‘Are you okay, mate?’ Bon was staring into the distance. ‘There’s a tower just like that in Paris,’ he informed Mark, pointing at the Eiffel Tower. Mark decided it was time they got some sleep.

Just ten months after their debut, AC/DC released theirsecond album, T.N.T., featuring Bon’s classic ‘It’s A Long Way ToThe Top (If You Wanna Rock’n’roll)’. And the band’s manager, Michael Browning—the man who brought Compulsion to Melbourne—had organised an international deal.

AC/DC might not have become AC/DC if not for Michael Browning. He was a believer. And Michael ’s venues— Bertie’s, where he booked the bands, and Sebastian’s, which he co-owned—were instrumental in the development of Melbourne’s music scene. He could have written a book just on Sebastian’s. We had so many great times there. I particularly remember the night Barry Humphries turned up dressed like the Hamburglar: he walked up the stairs and surveyed the scene, then hissed, ‘Fucking peasants,’ and walked out.

In 1975, Bon invited Gab and me to a gig AC/DC were doing at Melbourne’s Hard Rock Cafe, which was at the site of the old Bertie’s, on the corner of Spring and Flinders streets. Bon greeted us when we arrived, and beamed as he hugged me.

‘Mate, we’re doing it,’ he grinned. ‘We’re going to England. I want you to come.’

‘What?’ I wasn’t sure if I’d heard right.

‘We’re going to England, mate. I want you to come with me.’ This was what we’d both dreamed of. All those nights spent smoking at that little Toorak Road f lat, talking about how we

wanted to take an Aussie band overseas and kick arse.

I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

I understood where Bon was coming from. He knew it was a long way to the top and touring overseas wouldn’t be easy. He dug his new band mates, but he was also aware that he came from an almost different generation, as he was so mucholder than Malcolm and Angus. Bon wanted to have a matewith him; someone who knew him and someone he trusted.

Bon was growing into the rock star we always knew he would become, and that can be a dangerous time. When you’re famous, everyone wants to know you. But are they your friends just because of your fame? Bon and I were mates when he had nothing but his talent and his street smarts. We’d slept in vans together. I knew how he functioned. I could read him on stage. A good roadie can watch a band and know what they need, often even before they know.

‘So, can you come with me?’ Bon asked.

So many things were rushing through my head. I loved Bon and I knew how much fun we would have on the road. But then I looked at Gab and thought about how much I loved her and our baby daughter, Bec. Having come from a broken home myself, I didn’t want to see my own kid deal with all of that. And I knew that if I went with Bon and AC/DC, I might never come back.

‘Mate,’ I said, my voice quivering, ‘I can’t . . . I can’t go. I’m sorry, mate.’

Bon looked at Gab and he understood. He used to call Gab and me ‘Ma and Pa Kettle’, and while I thought he was living the dream, I think he thought Gab and I were living the dream.After telling Bon my decision, he had to go on stage. We both had tears in our eyes, but the show must always go on.

Michael Browning spotted me as I walked away. ‘Hey, mate,’he smiled. ‘Come into the office.’

I followed him, and found Bill Joseph, The Valentines’ old manager, also there.

‘Bon wants you to come overseas with us,’ Michael said.

He was surprised that I didn’t look happy.

‘I know,’ I replied. ‘I’ve just told him I can’t go.’

Michael and Bill could see how disappointed I was. They also knew there was nothing they could say that would change my mind.To go on the road and look after Bon, or stay home and look after my family: my mate, or my wife and daughter? It was a horrible dilemma.And I’ve thought about it every day since.