13 great feuds between artists and record companies

Amanda Palmer fired off a song directed to Roadrunner Records: ‘Please Drop Me.’ ‘Jimmy Iovine’ from Macklemore & Ryan Lewis’ The Heist album about the famed label exec spat out: “Cause all I ever dreamt about was makin’ it/They ain’t giving it, I’m taking it.”

On ‘Don’t Let Me Get Me’, Pink name-checked another legendary label man, “LA” Reid, about her early days: “LA told me, ‘You’ll be a pop star, All you have to change is everything you are/ Tired of being compared to damn Britney Spears/ She’s so pretty, that just ain’t me.”

Against Me! commented on being on the label treadmill via ‘Unprotected Sex With Multiple Partners’.

The Clash complained about CBS on ‘Complete Control’, ‘80s Melbourne band MEO 245 lamented, “Why don’t they leave our dreams alone?” in ‘White Lies’, and The Sex Pistols grizzled about ‘E.M.I’.

Nick Lowe had sarcasm dripping on ‘I Love My Label’ and R.A. The Rugged Man swung out with ‘Every Record Label Sucks Dick’.

Last year it was Taylor Swift threatening to re-record her early hits as a result of her racca-pacca with Scooter Braun’s Ithaca Holdings. In 2019, Ithaca bought out Big Machine Records, the small Nashville label which discovered her in a café as a 15-year old and released her first six albums.

This year the fickle finger of fate fell on Texas rapper Megan Thee Stallion and Memphis performer Juicy J best known for his guesting on Katy Perry’s ‘Dark Horse’. Megan successfully took record label 1501 Entertainment to court claiming it peevishly refused to release new material after she signed with Jay-Z’s Roc Nation for management.

She further alleged that hostile social media posts about her came from 1501, which she also accused of releasing her mugshot from an arrest five years ago. Juicy J made similar accusations, of new music not being released, against Columbia Records.

He tweeted, “I gave Columbia Records 20+ years of my life & they treat me like back wash. I’m gonna leak my whole album, stay tuned.”

This was followed by a short music piece called ‘Fuck Columbia Records’.

Suddenly, all the tweets and the song vanished and Juicy told fans “Spoke to @ColumbiaRecords. We are all good!”

13 examples of artists clashing with their labels

(1) TLC hold Clive Davis hostage

TLC, the biggest girl band of the ‘90s, were mighty honked off that despite selling 65 million records, they were only making $75,000 apiece. The real problem was they had signed a deal which allowed their manager to own the name, and get a share of all earnings.

Undaunted by this triviality, TLC turned up to Arista Records headquarters – accompanied by some huge fearsome women that Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes had met in rehab – and barged into the offices of big boss Clive Davis.

He was in a meeting with P. Diddy, which abruptly terminated when the gals threw Puff out of the room. They then held Davis captive at gunpoint while their contracts were renegotiated.

Tionne “T-Boz” Watkins opened up on late night US TV: “They did give us some money, but they still took it back and recouped it, but it’s all good.

“You live and learn in the business.”

Watch TLC here:

(2) Frank Ocean plays chess

Blond ambition

Def Jam Records signed Frank Ocean in 2009, and then kept him on ice because it thought his style of R&B was too old hat.

But after the Nostalgia Ultra mixtape that Ocean paid for himself, generated a lot of boomwah in 2011, Def Jam got excited enough to push his debut album Channel Orange.

It debuted at #2 in the US (peaked at #9 in Australia) and was nominated for a Grammy. Now cashed up, Ocean began exacting revenge while he worked on a second album. He sacked his management, legal team and publicist.

He bought his master recordings and got out of his contract with one last release through Def Jam.

That was the ‘video album’ Endless, which came with the cruncher it was for release only on Apple Music, that the film could not be downloaded, and its 18 songs not streamed individually.

In other words, Def Jam was not going to make a hell of a lot of moolah out of it.

Two days after Endless’ release, Ocean issued his second album, Blond, paid for by himself and issued on his own label Boys Don’t Cry.

It debuted at #1 in the US, Australia and some of Europe, and earned Ocean $1 million in profits in its first week. Def Jam and parent Universal Music Group spat chips.

The singer told the New York Times of a “seven year chess game” to gain control of his career.

(3) Amanda Palmer goes belly up

Credit: Ash Mar

Amanda Palmer wrote ‘Leeds United’ about how she was always losing things – keys, wallet, even a prized Leeds United soccer jumper given to her by then-boyfriend Ricky Wilson of Leeds, England band Kaiser Chiefs.

But the beef she had with Roadrunner Records in 2008 was all over the video for it.

The label snipped a shot of her belly. Palmer blogged, “They thought I looked fat, I thought they were on crack.”

Eventually Palmer got her way, but not before scores of fans began a “ReBELLYion”, posting photographs of their bellies to her fan site Shadowbox, which were in turn sent to Roadrunner to make their point.

(4) The Scientists go to a go go

Blinding science

In March 1984, Perth originated post-punkers The Scientists relocated to London. They landed a European tour with The Gun Club, and made plans to release their next album You Get What You Deserve, in the UK in July 1985 on their manager’s Karbon label.

This came as an unwelcome surprise to their Melbourne-based Australian record label Au Go Go who had paid for those recordings. One of its owners Greta Moon flew to London and got the maser tapes back.

When The Scientists apparently would not cooperate, Au Go Go released its own version with remixed tracks called Atom Bomb Baby.

(5) Ooo ma ma mow mow, there’s a meaning there

When EMI Australia signed up Russell Morris in 1968 the plan was a sedate three-minute pop song as his solo debut. It was to be produced by EMI’s new in-house producer Howard Gable.

Morris and his manager and record producer Ian ‘Molly’ Meldrum had done a couple of record sessions in Melbourne but had rejected them to be fairly average.

The duo decided on a psychedelic pop song that Johnny Young had written with a band in mind, with some inner vision nonsense about, “there’s a meaning there but the meaning there doesn’t really mean a thing.” Er, whatever.

Gable hated ‘The Real Thing’ and wanted to go with a ballad called ‘The Girl That I Love’ which Young had also written. As luck would have it, he had to go back to New Zealand for four months.

So EMI agreed to, in the interim, pay for more recordings that Meldrum could produce, but made it clear the first single would only come from the earlier tracks which Morris and Meldrum had already rejected.

That was solved when the vocals on those tracks were, umm, accidentally wiped.

‘The Real Thing’ turned into a statement about political saviours so Meldrum and engineer John Sayers stretched it out to a six minute meldrumatic freak-out with sitars, piano rolls, Hitler and Churchill speeches, a German choir, and the atomic bomb.

See the video here:

EMI HQ in Sydney was getting studio bills amounting to $10,000 ($121,825 in today’s money), which is what a whole album cost then. When executives realised to their horror it was just for one track, it was decided to throw Meldrum off the project.

Two execs were dispatched to Melbourne to seize the tapes. There are various versions as to what came next. But it involved Meldrum, dosed on brandy in anticipation, grabbing the tapes when the EMI dudes arrived at the studio and jumping over the fence almost knackering himself.

A search party found him in the dark hiding in some bushes with the tapes. EMI seemed reluctant to promote it, so Morris and Meldrum drove up to Sydney in the singer’s clapped out Volkswagen, stopping at every radio station on the way to deliver copies.

Many put it on air as soon as they heard it. ‘The Real Thing’ went to #1 for six weeks, and in the last 50 years been used extensively in ads and made EMI far more than its $10,000 investment.

(6) Joss Stone gives up her fortune for independence

Joss Stone was hailed as one of the best young soul voices to come out of Britain. By 2009 she released a single on which she sang, “Free me, free me, EMI.”

After the label was bought out by a private equity firm in 2007, she complained she had “no working relationship” with the new owners. When her fourth album flopped, she decided it was time to take matters into her hands – she bought herself out of the contract.

She was worth $22.5 million at her peak, having sold 17 million albums and with her acting in films (Eragon, Snappers) and on television (The Tudors, in which she played Anne of Cleves).

According to Stine, she gave up most of her fortune to gain her freedom. “It all went when I left EMI,” she said. “I was flat even, down to nothing. I wasn’t even down to a million in the bank…

“What I had left was my house and three flats in Exeter and that was it. Money is the thing that people hold over you but to me it was just cotton balls. Don’t let it suffocate you. Don’t let yourself need it that much.

“I just thought, ‘I’m free. I’ll go out and play some gigs and earn my living’.”

See the in action here:

(7) John Fogerty runs through the jungle

There was no love lost between John Fogerty and Saul Zaentz, boss of his previous band Creedence Clearwater Revival’s label Fantasy.

In a 1985 solo album Centerfield, Fogerty included two tracks, ‘Mr. Greed’ and ‘Zanz Kant Danz’, obviously aimed at the executive.

Zaentz got his revenge. He claimed Fogerty’s single ‘Old Man Down The Road’ was a rewrite of Creedence’s Fogerty-penned 1970 hit ‘Run Through The Jungle’ which Fantasy owned.

In what had the music industry blinking, in 1988 he launched a copyright infringement case. Fogerty won but paid out $1.35 million in costs.

Watch the video here:

Fogerty told The Guardian in 2000, “I was sued for sounding like myself, and people tell me this was unprecedented. I spent more than three years trying to resolve these issues, but sadly it didn’t work.”

A separate defamation case by Zaentz over the two tracks was settled out of court.

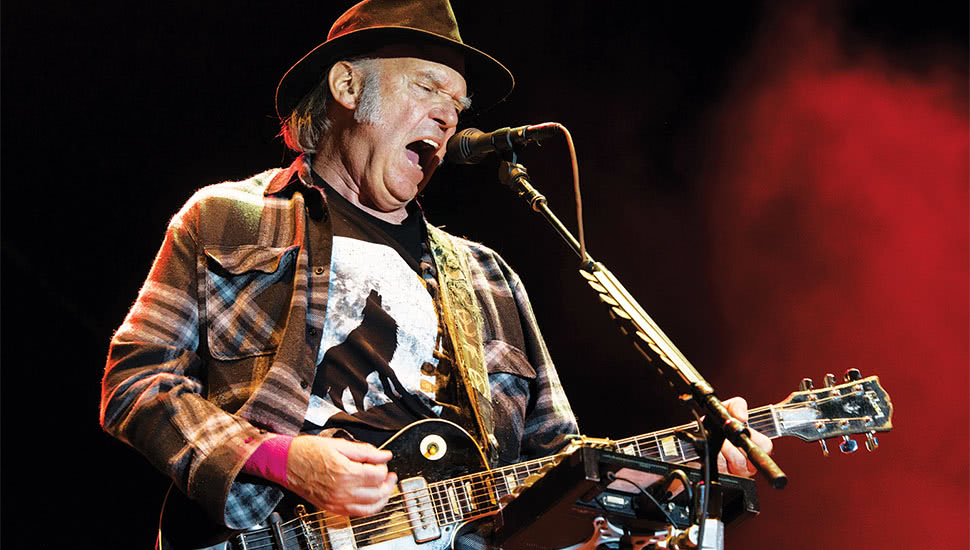

(8) When Neil wasn’t being Young

When I was Young

If John Fogerty was sued for sounding like himself, Neil Young was done for not being Neil Young enough.

In 1982, when Geffen Records signed him, it gave him $1 million per album and total creative control.

It was expecting more of the glorious folk-rock slabs and fuzzy guitar rockouts like ‘Cinnamon Girl;, ‘Ohio’, ‘Old Man’ and ‘Heart of Gold’. Alas… and you knew there’d been an ‘alas’ with Young… Neil was going through a period of experimentation.

Island In The Sun, made in Hawaii, was “a tropical thing all about sailing, ancient civilisations, islands and water,” according to the great man.

He was at the time working on a therapy program for his young son Ben who was born with cerebral palsy and unable to speak.

Hence Re·ac·tor and Trans albums were repetitive with distorted vocals, and abounded with a newly acquired Synclavier and vocoder. At which point Geffen decided it was time to speed-dial their lawyers.

(9) Tame Impala and the Modular model

Kevin Parker photo by Matt Sav

During a Reddit AMA in April 2015, Tame Impala leader Kevin Parker stated: “Up until recently, from all of Tame Impala’s record sales outside of Australia, I had received…. zero dollars. Someone high up spent the money before it got to me.”

Copping the heat was Steve Pavlovic, founder of Modular Recordings, one of the coolest labels to come out of Australia.

Modular and Universal Music Australia were sued that year in a New York court by rights management organisation BMG over US$450,000 in royalties not paid to the band.

BMG had issued a “mechanical license” to Modular in March 2014, which meant the latter could distribute the early EPs but not own it.

Pavlovic told Billboard, “The issue arose out of an unfortunate misunderstanding due to their being different ways of calculating and paying mechanical royalties in the US compared to the process we were used to in the UK and Australia.

“We didn’t realise that the different statutory process in the U.S. required Modular to deduct and pay the artists’ mechanical royalties directly.”

Confusing the issue was the fact that Universal was at that time buying out Modular, and there was a squabble over terms. That went to court in NSW, and ultimately Pavlovic left the label he founded and which discovered Wolfmother, The Presets, Ladyhawke, The Avalanches, Cut Copy, Bag Raiders and Sneaky Sound System.

(10) Backstreet Boys weren’t Zomba favourites

In 1999, the Backstreet Boys extended their deal with Zomba for two further albums, with the second to earn them $5 million if it arrived on time. However by the time of the second album, the band complained Zomba was too busy on a Nick Carter solo album and not taking much interest in them.

They were also peeved that Zomba used their website and mailing database to market Carter.

The result was a $75 million lawsuit in 2002 against Zomba, which also demanded their contract with the company be torn up.

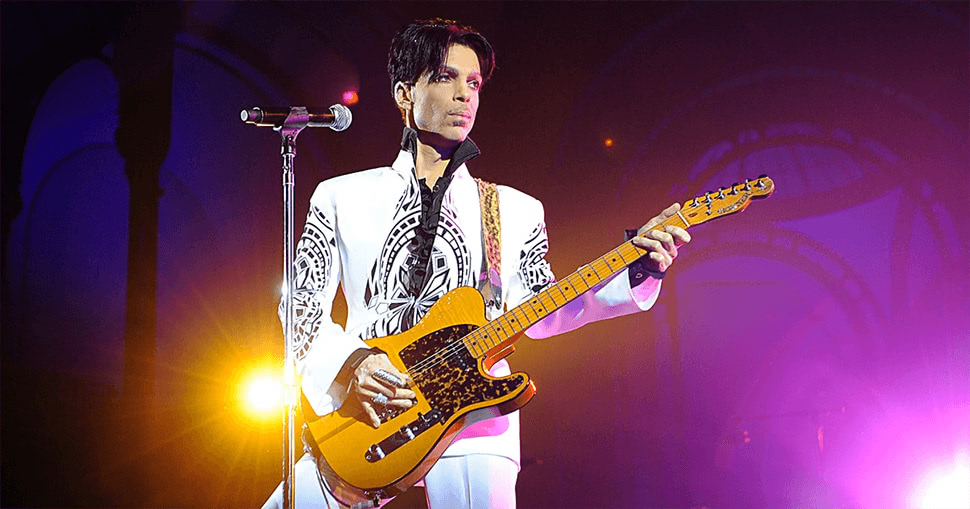

(11) Prince’s symbol mind

Slave to the rhythm

The daddy of the record company feuds – Prince versus Warner Brothers.

When he signed to them in 1992, it was a time Janet Jackson and Madonna were landing massive deals. To overtake them, Prince went for a six-album $100 million deal.

So much money meant of course that the label had more control of his rights and music than what the purple one expected. When the prolific genius kept hammering out albums in rapid time, the company told him to slow down, because saturating the market was tarnishing his brand.

Prince took this well… not!

He changed his name to Love Symbol and Glyph because those weren’t the names on his contract. That didn’t void the deal but he set a precedent by demanding he own his master tapes.

He said at the time, “The company owns the name Prince and all related music marketed under Prince. I became merely a pawn used to produce more money for Warner Bros.”

During the seven-year feud, he took to turning up at public events with ‘Slave’ scrawled on his cheek, and rushing out even more (often half-baked) albums in quick time.

He was the first main star to sell music online and mooted the now common practice of bundling concert tickets and albums. Three months after he finished off his Warner deal in 1996, he released a three-album set with the pointed title Emancipation.

And after all that, in 2014, he returned to Warner Bros to release the 30th anniversary of Purple Rain.

(12) Taking out the garbage

Lou Reed

So you’ve just had a huge hit and the record company wants more of the same, or you’re about to leave for greener pastures and the label wants you to finish off your contract.

What do you do? Give the execs garbage, of course, something so smelly they’ll run a mile.

Lou Ree came up in 1975 with the double album Metal Machine Music, 64 minutes of guitar feedback and effects, and released through RCA Records.

“Most of you won’t like this, and I don’t blame you at all. It’s not meant for you,” he said in the liner notes.

Hassled to come up with Pt 2 of his massive Tubular Bells, Mike Oldfield stuck it to Virgin Records with Amarok, which consisted of a sole track of genre-jumping and a morse code message “Fuck off RB” to Virgin founder Richard Branson.

Just as The Rolling Stones were to set up their own record label with Warner, Decca Records tapped them on the shoulder to say it was still owed a final single. No problem said Mick Jagger, who delivered them ‘Cocksucker Blues’ complete with references to fellatio, anal sex and beastiality.

In 1967 Van Morrison wanted to get out of his deal with Bang Records. After its founder, songwriter Bert Berns, died of a heart attack, Bang was taken over by his wife, who wanted more R&B/pop hits like ‘Brown Eyed Girl’.

Morrison went into a New York studio one fine day, and banged out the 31 songs needed to finish off his deal.

They were made up on the spot (on ‘Ring Worm’: “I can see by the look on your face / That you’ve got ring worm”), and were played on an out-of-tune guitar.

It did the trick. Morrison was dumped, and he moved on to a new label through which came the masterful jazz-inflected Astral Weeks.

(13) Reelin’ In this year’s model

In the early ‘80s, members of art-pop The Models and The Reels planned to put a band together called The Act.

Rehearsals were about to begin when, according to The Reels, The Models’ label Mushroom stomped on the idea. Mushroom denied it, via a telex sent to Juke magazine which reproduced it in its pages.

This article originally appeared on The Industry Observer, which is now part of The Music Network.